The Sources of Dark Intruder, by Rick Lai

(Watch Dark Intruder for free.)

If you watched horror movies on television as a teenager in the 1970’s, you would have watched them on some late night broadcast channel after midnight. In 1971, I stumbled across a little gem of a black and white thriller called Dark Intruder (Universal,1965). About nine minutes into the film, I was shocked to hear references to the gods of H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. As I watched the movie repeatedly in the decades that followed, I was surprised how cleverly elements from different pulp stories was mixed together.

If you watched horror movies on television as a teenager in the 1970’s, you would have watched them on some late night broadcast channel after midnight. In 1971, I stumbled across a little gem of a black and white thriller called Dark Intruder (Universal,1965). About nine minutes into the film, I was shocked to hear references to the gods of H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. As I watched the movie repeatedly in the decades that followed, I was surprised how cleverly elements from different pulp stories was mixed together.

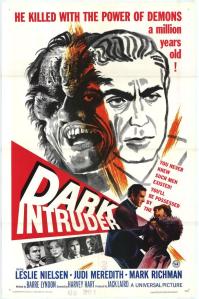

Running 59 minutes, the movie was actually an unsold TV pilot for an occult detective series entitled Black Cloak. The hero was Brett Kingsford (Leslie Nielsen), a wealthy dilettante who was secretly a supernatural expert. In the San Francisco of 1890, Kingsford formed a secret alliance with Police Commissioner Harvey Misbach (Gilbert Green) to assist against occult malefactors. Assisting Kingsford was his midget butler, Nikola (Charles Bolender).

When the film began, four people had been slain by a monstrous assailant with claws and a misshapen face. The newspapers compared the killings to the recent Jack the Ripper murders (1888) in London. Next to the body of each victim was a serpent-like ivory idol with a gargoyle growing out of the back of the skull. With each death, the lesser monster protruded further. Viewing the assembled idols at police headquarters, Kingsford had these comments:

“These are too good to be Voodoo, and they are not Egyptian. There are certain religions in the Hoggar region . . . the Crimson Desert . . . Azathoth . . . Dagon.”

Borrowing one of the idols, Kingsford took it to an elderly Oriental sage, Chi Zang (Peter Brocco), The elderly Asian identified the idol:

“This is a Sumerian god, ancient before Babylon, before Egypt. It is the essence of blind evil, with its demons and its acolytes, so cruel, so merciless. All were banished from the earth, and they are forever struggling to return.”

Chi Zang also asserted that the demons subservient to this Sumerian god can possess a human or an animal. However, this demon can only transfer his spirit to a more suitable host body if he performed seven ritual killings. These murders correspond to the seven spokes of “a demon’s wheel.” Chi Zang even showed Kingsford the baby-sized mummy of such a demon. It was a toad-like creature with claws.

Concurrent with the serial murders were the blackouts of Kingsford’s friend, Robert Vandenburg (Peter Mark Richman), a wealthy merchant who was preparing to wed socialite Evelyn Lang (Judi Meredith). Born in 1860 near Baghdad during an archaeological expedition, Vandenburg feared that he was the murderer because all the victims were either acquainted with him or connected with his place of birth. In order to gain some insight into these strange events, Kingsford consulted a book of arcane lore, The Cabala of Demonic Possession by J. Drail. Vandenburg sought assistance from an acclaimed psychic, Professor Malaki (played by Werner Klemperer, but his voice was dubbed by Norman Lloyd). Disguising his appearance by wearing a hooded robe, Malaki was actually the clawed killer.

Kingsford’s inquiries reveal that Vandenburg had a scar on his back from an operation done shortly after his birth. Vandenburg believed that just a lumpy patch of skin had been removed. In actuality, a stillborn deformed Siamese twin had been detached. A nurse, Hannah Nelson, had been entrusted with the disposal of the child’s corpse. A Sumerian demon then possessed the dead baby and brought it to life. Taking pity on a deformed infant, Hannah decided to raise the boy as her own. Upon reaching adulthood, the possessed Vandenburg twin became Professor Malaki in order to commit seven ritual slayings that would result in swapping his mind with that of his biological brother.

Following the death of the seventh victim, Malaki was able to switch bodies with Robert Vandenburg by invoking monstrous entities with the following incarnation:

“O Utuq, God of the Night . . Broosha, Ruler of the East .. Demons Asmodeus, Azazel, Maskim, and the banished gods Nyoghta and Garoth, aid your servant in the name of Shaitan and Opun, Father and Mother of Mindless Chaos.”

The sorcerer then slew his old body now housing Robert’s intellect. Deducing the monstrous crime that had occurred, Kingsford avenged his friend’s death by exposing the impersonation. The bogus Robert Vandenburg was fatally shot by Police Commissioner Misbach.

Writing in Weird Tales and other magazines during the 1920’s and 1930’s, H. P. Lovecraft created a mythology of cults worshipping the Great Old Ones, entities from the dawn of history. Eventually labeled the Cthulhu Mythos, Lovecraft not only fashioned his own uncanny deities, but drew in creations from earlier writers. The quote involving “the Hoggar region . . . the Crimson Desert . . . Azathoth . . . Dagon” is indicative of this fact. Lovecraft had invented such awesome beings as Azathoth, the mindless embodiment of Chaos, and Dagon, a grotesque elaboration on the Biblical fish god of the Philistines.

The Hoggar region actually exists in North Africa. In 1919, French novelist Pierre Benoit wrote a classic novel, Atlántida (French: L’Atlantide) in which a secret colony of Atlantis still survived in the Hoggar Mountains. Benoit’s novel was science fiction without supernatural elements. In a letter to Clark Ashton Smith (October 1, 1927), Lovecraft praised this novel. During October-November 1927, Lovecraft rewrote a story by Adolphe de Castro into “The Last Test.” Under de Castro’s byline, this ghostwritten tale was published in Weird Tales (November 1928). In his revision, Lovecraft transformed Benoit’s secret descendents of Atlantean colonists into worshippers of the gods of the Cthulhu Mythos. Besides the Hoggar Mountains, “The Last Test” also mentioned “an old man who had come back alive from the Crimson Desert—he had seen Irem, the City of Pillars . . .” Irem was a legendary city in the Arabian desert cited in both the Quran and The Book of One Thousand and One Nights. Lovecraft had first utilized Irem in “The Nameless City” (Wolverine, November 1921).

Lovecraft also allowed other writers to build on his mythology. Professor Malaki’s incarnation that climaxed his murder spree invoked “the banished gods Nyoghta and Garoth.” Nyoghta was a blob-like entity added to Lovecraft’s pantheon by Henry Kuttner in “The Salem Horror” (Weird Tales, May1937). Garoth was a winged Satan-like demon depicted by Lovecraft’s protégé, Robert H. Barlow, in three tales: “The Misfortunes of Butter-Churning” (Voyager 3, fall 1934), “The Temple” (The Perspective Review, Spring 1935) and “The Adventures of Garoth” (The Perspective Review, Summer 1935). All these Garoth episodes were reprinted in Eyes of the God: The Weird Fiction and Poetry of R. H. Barlow (Hippocampus Press, 2002).

Besides these creations of Kuttner and Barlow, Malaki’s spell also requested assistance from beings with a genuine foundation in religion or myth: Utuq, Broosha, Asmodeus, Azazel, Maskim, Shaitan and Opun. Utuq is a Sumerian demon that takes the form of larvae and burrows into its victims’ heads. Utuq was treated as the name for a race of demons in in Francois Lenormant’s La magie chez les chaldéens et les origines accadiennes (Paris, 1874). The book was translated in English in 1878 as Chaldean Magic: Its Origin and Development. However, Theresa Bane’s Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures (McFarland Publishing, 2012) claims Utuq (under the variant transliteration of Utuk) is an individual demon with the same attributes as the monstrous race described in Chaldean Magic. Derived from Jewish legends in Spain, Broosha is a she-demon that drains the blood of infants in the form of a cat. Broosha (more properly known as La Broosha) was an avatar of Lilith, the succubus who seduced Adam in Hebrew folklore. Asmodeus is the king of demons from the apocryphal Book of Tobit. Azazel, the leader of fallen angel who fathered giants with mortal women, is from the apocryphal Book of Enoch. La Broosha, Asmodeus and Azazel were all cited in R. Campbell Thompson’s Semitic Magic: Its Origin and Development (1908). Maskim (pronounced “Mus-keem” by Malaki) is actually a name for seven Sumerian demons that dwell beneath the Earth. Like the Utuq, the Maskim were discussed in Lenormant’s Chaldean Magic. Shaitan, the Islamic version of Satan, was also briefly covered in the same book. Opun is a demon mentioned once in The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, an actual tome of mystical rituals that dates back to at least 1608. Although cited as the Mother of Mindless Chaos by Professor Malaki, Opun’s gender wasn’t identified. Opun’s name is a Hebrew word for “wheel.” which fits into the prayer wheel concept of Dark Intruder. The Hebrew word is currently transliterated as “ophan,” a spelling which is more consistent with Malaki’s pronunciation of the demonic name (“O-phãn”).

Shaitan and Opun are depicted in Malaki’s incantation as “the Father and Mother of Mindless Chaos.” Lovecraft’s Azathoth was a mindless being living in the center of Ultimate Chaos. Mindless Chaos could be viewed as a synonym for Azathoth. Was the script claiming that Shaitan and Opun were the names of Azathoth’s parents?

The teleplay was written by Alfred Edgar (1896- 1872), a British writer who wrote under the pseudonym of Barré Lyndon. He was very experienced in writing about the fantastic. His 1939 play, The Man in Half Moon Street, was about a scientist seeking eternal youth through glandular transplants. It was first filmed in 1945 by Paramount under its original title, and then remade by Hammer as The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959). Lyndon (alias Edgar) had authored the screenplay for the 1953 movie version of The War of the Worlds. He also had a long association with fictionalizing Jack the Ripper. In 1944, he had done the screenplay for the adaptation of The Lodger, the novel about the serial killer by Marie Belloc Lowndes. During 1961, Lyndon adapted Robert Bloch’s “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” (Weird Tales, July 1943) for Thriller, a television anthology series hosted by Boris Karloff.

Bloch’s story advanced the premise that the Ripper was a sorcerer performing ritual murders to gain immortality;

“It is said that if you offer blood to the dark gods they grant boons. Yes, if a blood offering is made at the proper time —-when the moon and the stars are right—and with the proper ceremonies—they grant boons. Gifts of youth. Eternal youth.”

The reference to Jack the Ripper in Lyndon’s teleplay was not gratuitous. Lyndon was acknowledging Bloch’s tale as the source for the plot of a serial killer implementing an elaborate black magic ritual. There was another major borrowing from another of Bloch’s stories.

As one of Lovecraft’s correspondents, Bloch had written quite a number of Cthulhu Mythos tales. With its talk of “dark gods” whose power reaches its height “when the stars are right,” “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” was on the fringes of the Mythos. Bloch’s “The Mannikin” (Weird Tales, April 1936), a story about Siamese twins, was overtly linked to Lovecraft’s mythology.

The genesis of the tale can be directly traced to Lovecraft. In a “Commonplace Book” of proposed plots for horror stories, Lovecraft had this entry:

“Man has miniature Siamese twin—exhibit in circus. Twin surgically detached, disappears. Does hideous things with malign life of its own.”

Lovecraft passed along this idea to his fellow writer Henry S. Whitehead, who utilized the essential premise in “Cassius” (Strange Tales, November 1931), which replaced Lovecraft’s proposed circus setting with a Caribbean locale. Avoiding any link to the Cthulhu Mythos, the grotesque twin in “Cassius” resembled a frog-like creature about the size of a large rat. Once detached, the deformed twin attacked its fully grown brother.

With “The Mannikin,” Bloch tried his own variation on Lovecraft’s outline. Simon Mangalore was a supposedly hunchbacked poet. His hump was actually a miniature Siamese twin. Endowed with a malignant life of its own, the hideous twin was forcing his brother to study black magic and worship the gods of the Cthulhu Mythos. Although never explicitly stated, the story implied that Simon’s twin was demonically possessed.

Neither Whitehead’s “Cassius” nor Bloch’s “The Mannikin” employed the circus angle from Lovecraft’s outline. Bloch would rectify that omission by reworking the concepts of “The Mannikin” into “Unheavenly Twin” (Strange Stories, June 1939). Count Vomar was a sideshow freak with a miniature Siamese twin attached to his chest. Like Simon Malone, the Count was compelled by his twin to venerate demonic gods. These entities were only described as “the Others.” Unlike “The Mannikin,” Bloch avoided any obvious connections to the Cthulhu Mythos in “Unheavenly Twin.”

At the very least, Lyndon was probably familiar with “The Mannikin.” Besides “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper,” Lyndon had adapted Bloch’s “Return to the Sabbath” (Weird Tales, July 1936), a tale about Satanists terrorizing an actor in Hollywood, as “The Sign of Satan,” a 1964 television drama starring Christopher Lee on the Alfred Hitchcock Hour. Along with “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” and “Return to the Sabbath,” “The Mannikin’ had been collected in Bloch’s The Opener of the Way (Arkham House, 1945). Most likely, Lyndon read in this collection the two stories he dramatized for television.

Another homage to Bloch by Dark Intruder was the book consulted by Brett Kingsford. Among the fictional tomes of forbidden lore added to the Cthulhu Mythos by Bloch was the Cabala of Saboth, which debuted in “The Secret in the Tomb” (Weird Tales, May 1935) before reappearing in “The Mannikin.” Dark Intruder introduced a book with a similar title, The Cabala of Demonic Possession by J. Drail. The author’s name is an in-joke. J. stands for Jack, and Drail is an anagram of Laird. The producer of Dark Intruder was Jack Laird, who would later perform similar duties on Night Gallery (1970-73), a horror and fantasy anthology television series hosted by Rod Serling. Laird also wrote episodes of Night Gallery including a parody of the Cthulhu Mythos, “Professor Peabody ‘s Last Lecture.”

“Cabala” is a collection of mystical teachings with a basis in Jewish lore. The “Saboth” in the title of Bloch’s Cabala of Saboth is not a variant of Sabbath (“The Lord’s Day”), but a variant of Sabaoth, a Hebrew word meaning “Lord of Hosts.” While generally used in reference to God, the term Sabaoth could be used as a title for a leader of demons such as Asmodeus, Azazel or even Azathoth, whom Lovecraft portrayed as presiding over a demonic horde at the center of the universe. Lovecraft used the term Sabaoth inaccurately as a term for a feast day in “The Dunwich Horror” (Weird Tales, April 1929), a story about Yog-Sothoth, a cosmic monstrosity who mated with mortal women like Azazel in the Book of Enoch. The name “Adonai Sabaoth” was used in an incantation to summon demons in Eliphas Lévi’s The Mysteries of Magic (1886). Lovecraft used this “Adonai Sabaoth” spell in “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward” (written in 1927). Since this short novel wasn’t published until 1941(serialed in the May and July 1941 issues of Weird Tales), the only work by Lovecraft that might have influenced Bloch’s usage of Saboth/Sabaoth is “The Dunwich Horror.” Perhaps Bloch intended Saboth to be an alias for Azathoth or Yog-Sothoth.

Robert Bloch’s writings may also been the inspiration for the inclusion of Asmodeus in Professor Malaki’s incantation. Two of Bloch’s Mythos tales collected in The Opener of the Way, “The Faceless God” (Weird Tales, May 1936) and “The Dark Demon” (Weird Tales, November 1936) connected Asmodeus to Lovecraft’s deities. Both stories centered on Nyalathotep, whom Lovecraft depicted as the “Messenger” of Azathoth and the other Old Ones. “The Faceless God claimed Nyarlathotep was “the emissary of Asmodeus and darker gods.” Contradictorily, “The Dark Demon” made Asmodeus an alias for Nyarlathotep.

The usage of Azazel in Malaki’s spell may also gave been prompted by another Bloch’s story, “The Weird Tailor” (Weird Tales, July 1950). The tale involved the construction of a suit based upon specifications printed in a book of magic spells. The tome was described as a “volume printed in heavy black-letter German.” The unnamed grimoire featured “strange names—Azaziel, Samael, Yaddith.” Azaziel is a variant name for Azazel. Samael, also known as the Angel of Death and The Poisoned Angel, is another demon from Jewish folklore. Yaddith is a name of a planet in the Cthulhu Mythos. Lovecraft had originated the world in his sonnet cycle, “Fungi from Yuggoth”(written during December 1929- January 1930), but didn’t expand upon the imaginary world until “Through the Gates of the Silver Key” (Weird Tales, July 1934), a collaboration with E. Hoffmann Price. The brief Yaddith reference makes “The Weird Tailor” a very marginal Mythos story. However, Bloch later adapted the story for the Thriller TV series in 1961. The nameless German book was replaced in the teleplay by Bloch’s more famous Mythos prop, Ludvig Prinn’s De Vermis Mysteriis (Mysteries of the Worm). Written in Latin, Prinn’s treatise is probably Bloch’s most important contribution to the Mythos. Bloch further augmented the Mythos elements by transplanting the Latin incantation (“Tibi, magnum Innominandum, signa stellarum nigrarum et bufoniformis Sadoquae sigillum”) from “The Shambler from the Stars” (Weird Tales, September 1935) into the opening scene of “The Weird Tailor” television drama. You will have to listen very closely, but that is indeed the spell mouth by actor George Macready to summon a misty being inside a pentagram. Bloch’s teleplay removed the Azaziel reference, but Lyndon could have read the original tale.

Dark Intruder took the idea of a sorcerer transferring his mind to other bodies from H. P. Lovecraft’s Mythos story, “The Thing on the Doorstep” (Weird Tales, January 1937). The wizard in that story, Ephraim Waite, had a thoroughly human appearance. Malaki’s monstrous physique may have been prompted by a creature from “The Horror in the Museum” (Weird Tales, July 1933), a story that Lovecraft ghosted for Hazel Heald. There was a brief appearance by a “dimensional shambler,” a being depicted with a “rugose, dead-eyed rudiment of a head” and “talons spread wide.” This description could be applied to Malaki as well as the miniature mummy owned by Chi Zang.

In “The Thing on the Doorstep,” the spell for mind transference could be found in the Necronomicon, Lovecraft’s fictional book of arcane knowledge. Dark Intruder may have been responsible for inspiring one on the most famous hoaxes involving the Necronomicon. While Lovecraft and other writers had tied their fictional gods to ancient civilization like the Egypt of the pharaohs, none of them had done really anything with Sumeria. The Sumerian connection to the Great Old Ones was a clever innovation in Lyndon’s teleplay.

In 1977, a man known only as Simon produced a hoax Necronomicon composed of Sumerian rituals. Originally published as a limited hardcover, it appeared in 1980 as a mass paperback published by Avon Books. In a complex introduction, Simon attempted to equate Azathoth and other Mythos gods with the Sumerian pantheon. One wonders if Simon was inspired to do so by viewing Dark Intruder

Possibly Lyndon got the idea for a Sumerian connection from August Derleth. “Riders of the Sky” (Weird Tales, May 1928) by Derleth and Mark Schorer concerned an American archeological team being destroyed by Sin, the Sumerian moon god also known as Nanna. The story invented a Sumerian moon goddess, Ai, who returned in another Derleth-Schorer collaboration, “The Vengeance of Ai” (Strange Stories, April 1939), another tale of archeologists punished for violating the shrines of ancient gods. Ai became a deity linked to the Cthulhu Mythos in Derleth’s “Beyond the Threshold” (Weird Tales, September 1941). Lyndon had some familiarity with Derleth’s work. In 1961, Lyndon adapted “The Extra Passenger” (Weird Tales, January 1947), a story written by Derleth under the pseudonym of Stephen Grendon, as part of a Thriller episode called “Trio for Terror.” “The Extra Passenger” was a non-Mythos story about a murdered sorcerer exacting revenge on his killer.

Lyndon’s probable influence by Derleth can be seen in Chi Zang’s depiction of a nameless Lovecraftian god as an evil being banished from the earth. Lovecraft originally depicted his Great Old Ones as cosmic entities who were awakening from hibernation caused by the movement of the stars. Mankind’s inevitable destiny was to be destroyed once the Old Ones fully reawaken. Derleth had modified these concepts to have the Old Ones imprisoned and exiled by an apparently benign opposition, the Elder Gods. In Derleth’s version of the Mythos, the resurgence of the Old Ones was being constantly delayed by the magic of the Elder Gods.

Since Dark Intruder is essentially a classical detective tale in occult trappings, it ultimately has a Derlethian world view. The traditional detective story was about how an orderly society was disrupted by a crime. An heroic sleuth then restores stability by exposing the criminal. Nevertheless, Lovecraft’s pessimistic interpretation of the universe can still be glimpsed in Dark Intruder. Brett Kingsford may have defeated Malaki, but his victory was pyrrhic. Robert Vandenburg was destroyed, and Malaki’s masters still threaten mankind.

***

Article by Rick Lai.

Links to view some of the films and television episodes discussed.

2) Thriller – “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper“

3) Thriller – “The Weird Tailor”

Pingback: Movies Till Dawn: Chills in Springtime | The LA Beat·

Reminds me of the X-Files episode about a diminutive animalistic killer that is the “twin” to a circus performer that eventually returns and kills his older brother. Basically Lovecraft’s idea made real in the 1990’s.

I want to see this. I hope I can one day.

LikeLike

I can’t believe I’ve never heard of this film before now. Great find – it was a lot of fun – like the other commentators said, it’s something like an early version of “Kolchek, the Night Stalker”, and it looks like it would have made a fun television series – nice writing, nice production values, and it’s only about an hour long, but moves along at a faster pace than some some 45-minute long television shows I’ve seen. The show was produced by Jack Laird, who would later go on to insert Lovecraft references into Rod Serling’s “Night Gallery”.

LikeLike

This is a definite “must watch”. Thanks for the post, Mike. And kudos to Rick Lai on his excellent and exhaustively researched article.

LikeLike

What a shame this was not picked up as a series. It is like an earlier version of The Night Stalker. Thanks for alerting us to this gem.

LikeLike

I’m a HUGE fan of this film, and wish that Nielsen had more opportunities to play more serious roles (although it seems like the man was born to play comedy!). I discovered Dark Intruder several years ago, and keep hoping that someday we’ll see a proper DVD release. SOLID article!

LikeLike

It’s a fun little film, and would have made an interesting series, I think.

I had realized the film had distinct Bloch and Lovecraftian overtones, but certainly hadn’t researched it to the marvelous extent Rick Lai did.

Great piece.

LikeLike

Before Leslie Nielsen found his career as a great movie comedian he was one of the kings of tv drama. Sometimes he played the leading man, but most often he was cast as the suave badguy, appearing on shows such as Mannix, P.I. (probably mispelled, sorry), Ironside, and Columbo. I have never heard of him being in Dark Intruder, so I’m going to definitely try to look it up. I’ve seen the other four shows on your list, my favorite being Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper on Thriller. Thanks for another informative article 🙂

LikeLike

Oh, that sounds excellent! With Leslie Nielsen? Great find. Already loving the intro.

LikeLike