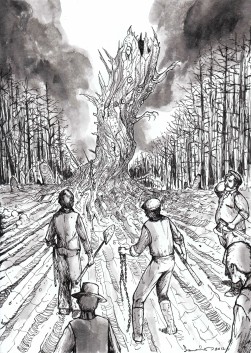

Click to enlarge. “Yule Log” — illustration by Peter Szmer: http://peterszmer.deviantart.com/

The log had not come willingly from the earth. It was if the roots at its base had gripped the peat in a fist of refusal. All the men on the estate had found themselves called to assist: pounding with mattocks, hauling on slippery chains or seeking a purchase on the slimy surface of the wood to drag it from its resting place deep in the bog. There was even the suggestion made of bringing in horses from the field, but the estate manager O’Rourke had vetoed this idea. Two men were injured during the labour, one with a dislocated shoulder, the other thanks to a pulled tendon in his calf, and O’Rourke didn’t want to put valuable animals at risk of also going lame.

The log was jinxed, no question about it, but it had become a matter of pride not to give in to it. What can you expect, several of the men said, from violating the land of The Old Gentry themselves, right there beneath the cursed rings of the Fairy Rath itself? O’Rourke was too much a Connemara man to laugh at their superstitions but too practical a one to take much notice of them. He grimly urged on the work as if it were a personal contest between him and the stubborn earth. When, after hours as it seemed, the log lay at last upon the heather, just four feet or so in length and half that across, he stroked his red shovel-shaped beard and glared at it in disgust.

‘Who’d have thought that would have taken so much hauling upon?’ he said, and added: ‘Sure, it looks just like a big black slug.’

The wood glistened with the slime of centuries, ebonised almost to fossilisation by the long years it had lain beneath the bog.

‘It’ll be as hard as stone to chop but it’ll burn with a fine light when you’ve managed it,’ said Donal, one of the older farmhands, flexing and unflexing his weary fingers as if keen to begin the execution there and then.

‘I doubt his lordship’ll consider the trouble to fetch it out was worth it, what with two men now unfit to work,’ rumbled O’Rourke.

‘Ah, but just think what a grand Yule Log ’twould make,’ said one of the young lads who’d been called in to help. O’Rourke clapped the boy on the back for having such a happy thought. The cutting of the annual Yule Log was one of the highpoints of the Christmas ceremonies kept at Glenshee, the centuries-old mansion on whose estate they were employed. Usually it was culled from the Derry Copse, a nearby stand of ash trees which represented one of the few remnants of ancient woodland then surviving in western Ireland. But there was no reason why a hunk of bog oak should not do just as well, indeed even better.

‘It’s just the right size to fit the big old fireplace,’ said Donal; ‘at least, if you keep its roots on. And it’ll burn for an age! I’ll be bound it’ll still be aflame the other side of Twelfth Night.’

‘You’re not wrong,’ said O’Rourke, rubbing his hands together with enthusiasm, looking for all the world as if he was already warming them by its light. ‘It’ll also save making further damage to the sparse old copse. Come on you men, let’s get it to the house.’

The procession of the Yule Log from Derry Copse to Glenshee was normally a jovial one, the men bawling out hymns as they hauled it along, a small boy as like or not riding on its back and geeing them along with shrill encouragement. This was a more solemn affair and, like the removal of the stump from the soil beforehand, one that was much harder work and took much longer than it had any right to. To make matters worse, a steady downpour had begun as soon as they had started to drag the wood away, and minutes later a chilly mist had rolled in from the ocean a mile to the west.

‘Are ye sure this blasted log hasn’t turned to coal already?’ grunted one of the men. ‘It weighs a ton.’

‘The roots keep catching on the stones and things,’ explained the youth who had made the suggestion of keeping the log for Christmas. He was jogging along beside it as the men hauled it through the heather. ‘Sometimes it looks like they’re doing it on purpose. They’re like thin long fingers. I swear they’re making grabs for the bushes and the boulders.’

The boy was, of course, ignored.

Fortune favoured O’Rourke when the gang reached the manor house. His master, Lord Killernan, was in the courtyard hearing the explanations and complaints of the injured men, who had been sent on ahead in a wagon. O’Rourke took a deep breath, anticipating a severe reprimand for failing to prevent their injuries. However, the storm had put an abrupt end to the morning ride of the two ladies of the house and brought their early return. Lady Killernan and the Honourable Cora’s enthusiasm for the arrival of the Yule Log had the effect of curbing his master’s displeasure.

‘Damned fools,’ snapped Lord Killernan, to his overseer’s relief. ‘Should have been more careful. A tough tussle, eh?’

‘Yes, my lord,’ said O’Rourke. ‘Worse than trying to free that stubborn bullock from the Furbogh Bog. Though I can’t understand the reason for it.’

‘The good doctor’s coming for dinner so he can give the fellows a look-over then,’ added Killernan. ‘Clumsy oafs.’

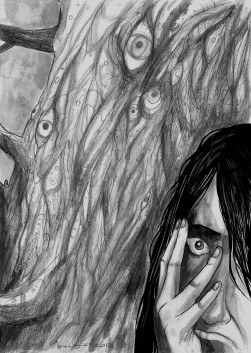

Click to enlarge. “Yule Log” — illustration by Peter Szmer: http://peterszmer.deviantart.com/

The lord of Glenshee manor was in his middle forties, a sparely built man with a moustache too large for his narrow face. Conscious of his unimpressive stature, he had long ago adopted a brusque and irritable manner in a bid to compensate for it. In contrast, his wife, Lady Margaret, was a handsomely built matron who wore her age and her figure well. It was perfectly suited to the full-busted, long-skirted fashions of those days just prior to the outbreak of the First World War. Lord and Lady Killernan’s only child Cora at 20 was one of the acknowledged beauties of Galway. Willowy and raven-haired, her finely sculpted features made her appear aloof, even haughty, until she smiled, which fortunately was often. Cora was in raptures over the arrival of the Yule Log.

‘It makes me feel Christmassy already,’ she said. ‘And it’ll burn well and slowly, too: the old bog oak always does.’

‘It’ll need a good wipe down,’ pointed out her mother. ‘It should be left in an outbuilding to dry off before we bring it into the house.’

‘It’s wet all right,’ said Cora. ‘Has anyone noticed the fish scales on it?’

Cora crouched down before the log and ran her gloved hand along its length. The men gathered round her.

‘Did you see this O’Rourke?’ she asked. ‘There are u-shapes, sort of chevrons, chiselled along it. And I’d swear that’s an eye carved at this end. All in all, what with those wavy roots streaming out behind it, it has all the appearance of a great fish.’

O’Rourke stooped over the girl’s shoulder but admitted he couldn’t make out the markings. Doubtful muttering from the men suggested they too were unable to see the pattern.

‘You’re not all blind, surely?’ said Cora.

‘Now, now, stop making your glove all filthy,’ admonished her mother. ‘Maybe when it’s dried out a bit we’ll be able to see it more clearly. Come along into the house now.’

Several hours later the local GP Dr Neligan joined Lord Killernan in the stable yard to enjoy a cigar and to take a look at the Yule Log. Earlier he had relocated a popped shoulder, bound up a sprained ankle and seen to one of the stable lads, Joey Murphy, who had suddenly come down with a fever, so had felt justified in making a good dinner. He was now overstuffed with pork and port. This did not prevent him from noticing how cold the night was, however. He shivered as tongues of fog curled around the stable doors.

‘This is unseasonably bitter even for a Galway December, my lord,’ he said. ‘The cold appears to have distressed the horses, too.’

From behind a number of the stable doors could be heard muffled whickering and the stamping of hooves on straw and stone.

‘I’ll have to get the lads to see about some blankets,’ said Lord Killernan. ‘The log’s in this small byre on the end. Let’s not linger long, Neligan. I just thought you might like to take a look at it, considering your antiquarian interests.’

If anything it seemed colder inside the lean-to than it did outside. The men’s breath blended with the smoke of their cigars. Dr Neligan raised his lantern and brought it up to where the Yule Log was lying along an old feeding trough.

‘Carvings, your daughter said?’

‘Fish-scales or somesuch,’ said Lord Killernan. ‘I couldn’t see them.’

‘No, nor can I.’

‘It’s my belief they were merely marks made by the men as they handled it. Young Joey gave it a good scrape earlier to get all the mud off. But perhaps if you run your fingers along it, you might be able to make something out?’

‘Yes, perhaps.’ Dr Neligan reached out for the log but then for a reason he was unable to explain to himself, let alone to Lord Killernan, he couldn’t quite bring himself to make contact with the log. There was something repellent about it. He was reminded of the time he was called to a body found washed up on the beach during his first year in practice.

‘I fear my fingers are too cold to feel anything,’ he laughed, to hide his embarrassment.

‘Perhaps we should return to the warmth of the house,’ said his host. ‘I’m afraid there’s nothing remotely archaeological about this lump. Although I believe it may be many hundreds of years old?’

‘Oh thousands, my lord, thousands,’ said Dr Neligan. ‘This old tree stump is a remnant of the great primeval forest which covered this land back in the Bronze Age, or possibly even the Stone Age, thousands of years before the birth of Christ. One can only imagine what the people were like back then, how they lived or how they worshipped. Who knows what loves, what tragedies may have been played out beneath its branches, or indeed what strange rites?’

‘You’re getting fanciful, Neligan,’ rasped Lord Killernan. ‘Let’s get out of this damnable cold.’

Dr Neligan followed his lordship out of the byre, shivering theatrically but warming to his subject.

‘You know, my lord, it will be dim memories of our distant ancestors that led to the belief in fairies so prevalent here in the west of Ireland. I understand the log was dug up out of the peat near the ancient hill fort?’

‘The so-called “Fairy Rath”, yes.’

‘Are you aware, my lord, that the fairies in this part of Connemara were once upon a time called the Fine an Domhain, or Tribe of the Deeps? They were believed to live under the sea, only coming on to land to steal away maidens or plant changelings among the peasantry. If ichthyomorphic designs had indeed been present on that ancient bit of wood, it would have been a thing worth recording.’

Dr Neligan received a cursory grunt in reply. Throwing away his cigar like a punkie-light in the darkness, Lord Killernan began to discuss the one topic that was then concerning the aristocracy of Ireland: would the Irish join the war against the Kaiser, or would it be better for them to see England defeated?

‘Even if the English are victorious, they’ll be greatly weakened by a war with Germany and that can only be good for Ireland,’ said Killernan.

‘They expected it to be all be over by Christmas, but that is proving absurdly optimistic,’ said the doctor.

‘Typical British arrogance. The Kaiser’s war machine is second to none in Europe in my opinion.’

‘Well, what will be will be: that old tree in there no doubt saw hundreds of years of conflict and resolution before it sank into the bog. Human life continues on regardless.’

This was an unfortunate comment for the doctor to make at that moment. As he made it, an elderly servant came hurrying across the yard, calling for him. The stable lad Joey had suddenly taken a turn for the worse; his temperature had risen dramatically and he had fallen into a delirium. By morning he was dead.

The death of the boy naturally caused a pall to fall over the Glenshee household. At his funeral, made more miserable by an onslaught of half-frozen stinging rain, one of the oldest servants muttered to her huddled companion something about the inadvisability of disturbing the land below the Fairy Rath. It was soon remembered that Joey had been the last person to touch the Yule Log: was it under a curse? That, they reasoned, would explain the strange behaviour of the horses, for they had continued their restlessness night after night.

On the night of the funeral a ghostly figure was seen to cross the courtyard and enter the byre where the log was kept. It was Cora Killernan, clad in nothing but a sleeveless gown of white satin. After his heart had started beating again, the farmhand who had glimpsed Cora gave a sigh of relief at recognising her, but became concerned when she failed to emerge again. What purpose could she have in the tumble-down shed? Had she too fallen ill? By the time he had told his tale to his curious colleagues, however, and they had followed him into the yard, Cora was striding back across to the main house.

This first expedition merited no more notice within Glenshee than a sharp rebuke from Cora’s mother for the imprudence of lingering out of doors on so cold a night without so much as a wrap to protect her: a mortally foolish act, she said, considering one young person on the estate had already died of what Dr Neligan had pronounced as a ‘chill’ (for want of a better explanation). The second instance, however, a few nights later, was taken more seriously. Cora lingered in the byre for more than hour. At one point soft singing could be heard from within: none, however, could discern the words she sang, and the odd, lilting tune was unfamiliar. The small crowd of employees who gathered in the yard to listen and wonder brought Cora’s presence to the attention of O’Rourke. As soon as the overseer appeared on the scene, the rest of the staff rapidly melted away. Cora emerged at almost the same instant. With a curt nod to the puzzled O’Rourke, she swept back to the house. He noticed that the fingers of her long white gloves were smeared with dirt.

O’Rourke said nothing of what he had seen and silenced the gossiping of his underlings. Nevertheless, word reached the ear of Lady Killernan, whose sharp admonishments were detected the next morning through the mahogany of the drawing-room door by a lingering maid, interspersed with the casual drawl of the daughter of the house. As far as was known, Cora thenceforth avoided the stable yard but her behaviour during the fortnight before Christmas continued to raise eyebrows. She took to long solitary walks along the stony beach half a mile from Glenshee, wandering through the sea mists and even facing down the savagery of the Atlantic gales, sometimes for hours. Although it never came to the attention of the household, Cora also continued her nocturnal expeditions: on two successive clear frosty nights, passing farm workers glimpsed her at the churning ocean’s edge, a tall white taper-like figure, her arms raised to a waxing gibbous moon, and these may not have been her only excursions.

Within doors she was frequently accused of ‘moping about’ by her parents or of otherwise ‘putting on romantic airs’.

‘She’s at that sort of age,’ Lady Killernan told her irritated husband. ‘She’s trying to be interesting and romantic. It’s pure affectation. She’s never without a volume of Yeats in her hand and I caught her reading Edgar Allan Poe, would you believe it, the other day. It’s just attention seeking, so far better to ignore it.’

‘Perhaps she’s in love,’ smirked Lord Killernan, and he seemed to think this a huge joke.

At last Christmas came round. The house of Glenshee was decked with evergreen and tinsel; gold and silver baubles gleamed among the glossy green of a spruce in the entrance hall; and parcels of all shapes and sizes, wrapped in expensive paper, tempted the eye and the imagination in the drawing-room. In this room, too, on Christmas Eve, the Yule Log had been brought amongst much pomp and ceremony and settled in the gaping mouth of its wide medieval fireplace. O’Rourke had found his men oddly reluctant to handle the old bog oak, so he had taken the honour on himself, along with Donal, a man who had served the Killernans long enough to remember the lighting of the Yule Log as a great tradition, one he had first witnessed fifty years before when, as a small boy, he had helped serve sweetmeats at the annual festive high tea.

Tea was now over. Cakes and buttered bread, blue cheese and mince pies had been cleared away. The gas was turned down low. Lord and Lady Killernan, Cora Killernan, Dr Neligan and several neighbouring farmers and their wives watched as O’Rourke brought a lighted fairing among the ash-chips and spruce-sticks that had been piled up under the Yule Log. The kindling smouldered, then crackled and the flames caught. The assembly applauded and O’Rourke and Donal withdrew, wishing the family and guests ‘Good night and a very merry Christmas’, which courtesy was but vaguely returned.

Flames of yellow and scarlet began to envelope the Yule Log. Cora rose and sashayed the length of the room to the fireplace, where she set up station, leaning on one arm against the mellowed stone of the arched surround, her head drooped to watch the interwreathing of smoke and fire.

Lady Killernan pretended to ignore this affectation, as she considered it, on the part of her daughter and instead complained: ‘It seems such a shame the men did not remove those straggly roots at the end of the log. It looks so untidy.’

‘If they had done so it would have failed to extend the width of the hearth, my dear,’ said Lord Killernan. ‘I’m sure they’ll be the first to burn.’

Crimson fingers now played over the log and the black oak seemed to smoulder from within. Cora suddenly turned to the room.

‘You see, there are eyes – and scales,’ she announced. ‘They’re being picked out by the flames.’

‘I think you’re just imagining it, my dear,’ countered Lord Killernan. ‘I’m sure it’s just the effect of the outer bark burning away.’

‘Don’t stand too close to the fire, Cora,’ added her mother. ‘You’ll spoil your complexion.’

‘Oh but it’s hardly giving off any heat.’ Cora pouted. ‘I can stand right up close. And there are eyes,’ she added. ‘And scales. And I do believe he’s smiling at me.’

Dr Neligan chose to be more indulgent. He leant forward in his armchair with an attitude of keen interest.

‘I’m afraid I can’t see what you see, Miss Killernan,’ he said. ‘But I have to say, what with that funny, helmet-shape at one end and those spindly roots at the other, the log seems less to resemble a fish than it does more some sort of squid.’

‘All very clever, I’m sure, but Cora, I must insist you stand away from that fire!’ snapped Lady Killernan.

‘I swear it’s getting colder in here, not warmer,’ said one of the farmers. ‘The wood must be water-logged. Look – it’s beginning to move on the grate. There must be steam escaping from it.’

However, no vapour was visible in the fireplace. At a further command from her mother, Cora stepped back a few feet and everyone was afforded an uninterrupted view of the Yule Log. It was indeed stirring. The flames smouldered down to a sooty yellow and in the subdued light the log could be seen to twist and throb on the coals. The company recoiled at the sight, staggering back in one accord as a primordial fear gripped their hearts. Only Cora remained unmoved.

The fire burned blue and a deathly chill fell on the room, as if the bog oak was absorbing rather than projecting the expected heat of the flames. The cold seemed to freeze tongues as well as bones. Nobody spoke, nobody moved. They were transfixed by the Yule Log’s contortions. It pulsed and writhed like a pupa about to burst into horrible life.

Suddenly the gas lamps too faded. Only the dim blue glow from the fireplace remained to show Cora falling to her knees before it. A communal gasp of shock went round the company as she tore open her white gown to reveal her fragile flesh, no less pale, beneath it. Her father lurched forward as Cora threw herself into an attitude of supplication, her arms outstretched, her body exposed.

But in that moment the Yule Log thrashed, leapt – and stood upright.

Its roots found purchase on the dying embers. Like the legs of a spider, it used them to creep over the fender, its tubular body teetering. Then it skittered across the carpet into Cora’s waiting arms.

Never more was The Hon Cora Killernan seen beyond the ancient four walls of Glenshee. The events of Christmas Eve, 1914, were unknown to any who had not then been present in the room. The farmers had been sworn to secrecy, under threat of summary eviction. The local gossip, however, was that Miss Killernan was in disgrace and so hidden away: there had been a clandestine affair and a child was the result. The existence of the child, at least, was a known fact – one could not keep such news as that entirely secret – and if there is a baby, then of course, reasoned the populace, there must have been a lover. The nature of that lover none could have guessed at.

Few saw the infant itself. None who looked upon it once wished to look upon it a second time. A nurse was brought from Dublin for its specific care. On the rare occasions this woman went abroad from Glenshee, she was recognised as a tight-lipped and forbidding individual. In the house itself they knew differently. On more than one occasion she was heard sobbing in the night. On other nights – sometimes on the same night – Cora could be heard crooning to the infant, warbling words unfamiliar and, to all who heard them, meaningless. Occasionally the child’s strange croaking laughter would be heard accompanying the eerie lullabies.

Then, one hot August morning just over a year after the baby was born, the Dublin nurse boarded a train from the little branch-line station and exited forever the sphere of Glenshee. Her place was taken by a psychiatrist, sent for, it was believed, all the way from London. The reason for his presence was soon found out: Cora had gone mad.

The night before had been notable for an almost tropical heat and a storm at sea which had driven the tide higher than any could recall before, the phosphorescent waves crashing almost to the gates of Glenshee. The same night had been disturbed by an unseasonable and unsettling chorus emanating from the distended throats of thousands of frogs and toads lurking among the moors and dunes. So loud was their vibrato that at times it swamped the rumbles of the distant thunder. Just before dawn the storm receded and the toads too stilled their unearthly din. Even then the tenants of Glenshee were kept from sleep, for the night was pierced now by crazed shrieks and wails from the mansion. It was Cora.

On that summer’s night in 1915, Cora’s child had vanished. Rumours abounded that it had been done away with, that its hideous deformities had proved too great a blight on the name of Killernan. Others more reasonably suggested it had been secretly taken away by the nurse to some distant sanatorium. But the oldest tenants had different ideas. Was there not now proof enough, they argued, that a curse had been laid on the house of Killernan for disturbing the fairy-haunted land below the ancient fort? Had not young Joe and in their turn the estate manager O’Rourke and old Donal all succumbed to some mysterious fever in the days following their handling of the ancient oak after it had been brought within the walls of Glenshee?

As for Miss Killernan, her fate was even worse, they said, for she had been delivered of a changeling, its grotesque appearance only too clearly revealing its true nature. That it had gone was in little doubt, for Cora’s wild and desperate cries for its return were heard more than once, shrieking from unguarded open windows. Whether her own family had removed it or it had been spirited away by its own people, the Fine an Domhain, was, however, open to debate.

Cora Killernan never again strayed farther than her own bed chamber and but rarely left her bed. Prematurely aged, her raven-black hair whitened by grief, she remained a demented invalid for the remaining twenty years of her life. But some secrets did not escape the house and reach the inquisitive ears of Glenshee’s gossiping neighbours.

On two nights of every year remaining to Cora – those of the high equinoctial tides – she was quiet and at peace. On the following mornings she would be found crooning softly and cuddling her pillow as if it were her long since vanished child. In her bedchamber the servants would discern a lingering odour redolent of wood-bound pools or festering sea wrack, and they would hurry to shut the windows, their noses wrinkling in disgust. Only one dared to mention the other oddity to be found in the room on those mornings and she was instantly dismissed for doing so. Crossing from the windowsill to the bed was a line of damp and swiftly fading footprints, wedge-shaped and six-toed: quite unlike any made by human feet.

Richard Holland lives in a former mining village in North Wales, UK, which is so old it was mentioned in the Domesday Book. He is a professional journalist and corporate copywriter and is the author of six books on British ghosts and folklore, with three more due for publication next summer. The former editor of Paranormal Magazine, Richard currently edits his own website devoted to ghosts and folklore, UncannyUK.com. He collects spooky old books, with shelves creaking under the weight of bound volumes of Victorian and Edwardian magazines. He is keen on golden age ghost stories and weird fiction by the likes of Blackwood, Benson, Burrage, Wakefield, Machen and M R James, as well as Lovecraft. The Yule Log is his first foray into writing fiction of his own for many a long year. Visit his Amazon author page here.

Richard Holland lives in a former mining village in North Wales, UK, which is so old it was mentioned in the Domesday Book. He is a professional journalist and corporate copywriter and is the author of six books on British ghosts and folklore, with three more due for publication next summer. The former editor of Paranormal Magazine, Richard currently edits his own website devoted to ghosts and folklore, UncannyUK.com. He collects spooky old books, with shelves creaking under the weight of bound volumes of Victorian and Edwardian magazines. He is keen on golden age ghost stories and weird fiction by the likes of Blackwood, Benson, Burrage, Wakefield, Machen and M R James, as well as Lovecraft. The Yule Log is his first foray into writing fiction of his own for many a long year. Visit his Amazon author page here.

Story illustration by Peter Szmer.

Richard check out the link above in regards to Pain’s story I mentioned.

Cheers.

MVA

LikeLike

Bibliophile, yes. Dramatic about what I love, guilty. Overgenerous? Never. This is a damn fine piece. I’m intimate with James’ work and have no life outside of reading 😉 and I’m almost 50, so this is a long love affair with fiction. I don’t say things like I did unless it is way beyond good. Like many others, I am a discerning reader. There are a lot of good stories out there, but not a lot of great ones. Take your compliment, Sir; and may it serve you well as you plan your next piece, for which I will be on the lookout.

(It’s gonna be hard to beat The Yule Log. It reminds me also of EF Benson and a tale The Undying Thing by Barry Pain of which Lovecraft was quite fond.)

Cheers

So glad you are writing.

MVA

LikeLike

Oh no, now you’ve compared me to Benson! This is too much. Yes you’re right The Undying Thing is a great story. I did realise halfway through that there was one story The Yule Log bore more than a passing resemblance to themewise. Indeed I considered trying to find out what ‘Lucky’s Grove’ might be reasonably translated to in Gaelic, so I could name the old coppice after it – but I decided I’d be unlikely to get a good enough translation and anyway it would be probably appear as trying too hard to be clever.

LikeLike

Well it’s sti a unique story, yours, what is it Harold Bloom wrote sbout in the 70s? The “anxiety of influence”. It’s an ubavoidable concept and one I think does wonderful good. Take care

LikeLike

Seriously good story. I think Mike Albright is right about the comparisons, and I also think your familiarity with supernatural lore shows here. It flows like one of the haunted castle stories we hear so often (on TV here in America), and there’s a seamless mixing of non-mythos and mythos folklore. And I love Irish English, it always seems to sing. Well done! Though I have to say, most awkward Christmas EVER!

LikeLike

Thanks very much for your kind comment. Yes, you’re right, there’s nothing worse than seeing your daughter kissing a malevolent phallic object under the mistletoe to put a damper on things.

LikeLike

Absolutely fantastic! It took me there, and I felt everything. Gorgeous!

LikeLike

Thanks William! I really appreciate your taking the time to give such a positive comment.

LikeLike

This story is so good I am a bit at a loss for words. It is right up there in time and theme sand quality with the best of MR James and Lovecraft. I was reminded as well of Derleth and Dickens and Austen. It just has so much. And to read this us a first foray into fiction for a long time. Some short fiction is good. Some is very good. But you can always find those odd items like irrelevant details or tonal shifts or the forced similie and misplaced metaphor. But then you get the pleasure of reading a piece of short fiction like something by Machen or James or Poe where not a word is wasted and each word and sentence snd paragraph is built one upon the other to form a little shining piece if art.

I am crazy in love with this story. It will have a place with the great ones that I collect and read again and again.

Exquisite.

MVA

LikeLike

Sorry about the typos I was excited. Typing too fast so I could hurry and read Yule Log again. 😉

LikeLike

Oh crikey, I don’t know how to respond to this. I’m so flattered. Even to be mentioned in the same breath as M R James makes me go goosebumpy, although I fear you are being overgenerous. I’m so glad you enjoyed it so much. I really will have to stop being so insecure and get writing more!

LikeLike

Pingback: My Lovecraftian story | Uncanny UK·

Just so long as you don’t camp on fairy-haunted land you should be fine, Mr Gibberer! And cheers for the encouraging comments, they’re much appreciated.

LikeLike

“‘She’s trying to be interesting and romantic. It’s pure affectation. She’s never without a volume of Yeats in her hand and I caught her reading Edgar Allan Poe, would you believe it, the other day. It’s just attention seeking, so far better to ignore it.’” – silly emo kids. I really liked this story. Really good job Richard! For now on I burn only the wood I bring to camp, and not the driftwood found near shore…

LikeLike

Excellent, Richard! Leaves me wanting to read more. I’ll have to be satisfied with reading it again, unless you plan to expand your story into a novel. I’d love to know details of how one goes about raising a sapling Yule Log.

LikeLike

Thanks Catherine! Seeds have been known to survive incarceration in ancient Egyptian tombs and still germinate, so maybe a seed of Fine an Domhain bog oak can still be nurtured – if you’re prepared to risk their wrath for disturbing the fairy-haunted ground!

LikeLike

Personally, this issue of Lovecraft eZine surely saved the best for last! Cheers, Richard, what a great read.

LikeLike

Oh, thank you Mark. Just the encouragement I need!

LikeLike