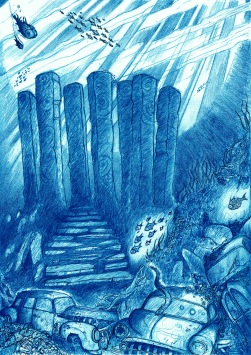

Art by Peter Szmer – http://peterszmer.com – click to enlarge

I stood beside the open grave smoking a cigarette. Not a good cigarette, mind you, but an old one, made stale by the passage of time. I gave up smoking months ago, and while the urge had finally caught up with me it had not overpowered my general laziness. Rather than investing in a fresh pack, I found the cigarettes I’d hidden behind the mouthwash in my medicine cabinet.

The cigarette tasted bad but it filled a need I’d almost forgotten. I savored the staleness because, if anything, it masked the rot wafting up from the ruined earth below. Elmwood was the oldest non-denominational cemetery in the city of Detroit. There were older cemeteries, lost and forgotten beneath the Babylon towers of development and decline. There were secrets buried beneath the concrete foundations of cities like Detroit. If you went digging long enough and deep enough those secrets were invariably uncovered.

My name is Daniel Blackwood. I’m a writer. At least I used to be. The publishers stopped calling when the words stopped flowing and past glories only last so long. I was never an artist but I was not a hack. Sloth became my agent, Pride my blinding better half. Once paired with ‘up and coming’ and ‘promising,’ the name Blackwood now found frequent affiliation with ‘whatever happened to’ and ‘wasted potential.’ I found it slightly ironic that the short story collection so enamored by my critics had been called Nothing of Consequence.

I knelt beside the grave, contrary dirt staining the silent snow. Indiscriminate piles framed the gaping wound like blood, brown and dark and kissed by the very death it embraced. The coffin sat silently still, seemingly undisturbed by the commotion my shovel had caused. I slid into the grave, found my footing on the smooth cherry surface and pulled the dead cigarette from between my dry lips. I buried it in the mud-stained snow and sighed.

Her name was Olivia. She was a goddess – not in the clichéd romantic sense but in the other, more literal sense of the word. After my creativity died, after my wife’s murder, I became a cryptotheologist. Don’t bother looking it up, I coined the phrase. Standing atop Olivia’s coffin, I suddenly wished to God I hadn’t.

I felt the book in my breast pocket, the words warm against my skin, tattooed there by conscience and constant memory. They were the words of the Psychomachia, words Prudentius wrote centuries before the surrounding soil saw the Sulpician likes of François Dollier de Casson and René Bréhant de Galinée.

I slipped the crowbar’s flat edge beneath the coffin lid. “Bastards,” I said. Casson and Galinée began everything when they found and destroyed a stone idol venerated by local natives.

Detroit was first mentioned by name in sixteen seventy when French Sulpician missionaries stopped at the site on their way to the mission at Sault Sainte Marie. Galinée’s journal noted that near the site of present-day Detroit they found and destroyed a stone idol venerated by the Indians, dropping its remnants in the river. French settlers later planted twelve missionary pear trees named after the twelve Apostles on the grounds of what was now Waterworks Park.

I cracked open the coffin, raised the lid and braced myself for the sickening scent of dampness and decay. It never came. The coffin lay empty at my feet. Silk, stained by seepage and soil seemed bereft of human remains. I found a small journal within the rotting folds of fabric. It was a leather-bound book wrapped in heavy cloth and written in French. With the book I found the stem of an old pipe upon which the name ‘Montreal’ had been stamped in black ink.

I tucked both the book and the pipe beneath my coat and crawled from the grave, cold and muddy and with an insatiable curiosity. The aging grave, marked only by a number on an antiquated cemetery map had allegedly housed the remains of Olivia Maloney. The daughter of Irish immigrants, Olivia lived and died in Detroit’s Corktown district more than a century ago. Rumors about the restless dead persisted in Corktown well into the twentieth century. Most died with the generations that spawned them, but stories about Olivia Maloney remained, albeit lost amidst the rubble of a neighborhood all but murdered by Progress.

The most importunate tales proclaimed her a banshee. According to Yeats, banshees were attendant spirits whose wailing lamentations preceded impending death. In a book on Irish fairies and folktales Yeats claimed these spirits followed the old families, ‘and none but them.’ If you bought into the local legends, these spirits followed families like the Maloneys from the old world to the new. The Irish were the first immigrants to reach Detroit en masse, escaping the poverty and oppression of the old world for the poverty and promise of the new. Olivia grew up in a row house on Howard, living the entirety of her brief life somewhere in or between the Trinity School for Girls on Porter Street and her uncle’s grocery store on Fort.

They tore the century-old Girl’s School down in the nineteen-fifties, erasing the past in order to pencil in a future that excluded Corktown. But it was there that she died, and there that the rumored hauntings began.

I left the empty grave and returned to my car. I dropped the shovel in the trunk and stopped to light another stale cigarette. I pulled the old journal and the accompanying pipe stem from my coat and placed them on the passenger’s seat before slipping back behind the wheel. The illegal excavation had exhausted me.

The bodiless grave was no surprise. Had there been a body, had that body irrefutably been Olivia Maloney’s, I would be hunting a ghost. I hadn’t come here searching for ghosts, at least not in the literal sense. As I told you before, I’m a cryptotheologist. I came here searching for a god – an old god – a god Casson, Galinée and the Sulpicians tried hiding centuries ago beneath the now murky waters of the Detroit River.

![]()

I brought the journal to a friend of mine. Although born in Quebec City he taught French at the University of Windsor. An avid bibliophile, Charles studied the crumbling journal over lunch at an artificially Irish pub on Chatham Street in Windsor.

He ran his finger through a name that bled watered sepia stains onto the heavyweight paper beneath it. “François Dollier de Casson,” he said. “The journal did not belong to Casson, but it was dedicated to him.”

He sipped his Heineken thoughtfully before reading the hand-written dedication. “François Dollier de Casson. ‘Que Dieu nous délivre du souvenir de ces visions.’ May God save us from all that we have seen.”

He gently turned the page. It was a simple, subtle act that revealed his reverence for the book itself, if not the words it contained. “Odd,” he mused. “The book is written entirely in French.”

“They were French.”

“Yes, but they were priests. I’d have expected Latin.”

If it seemed strange to Charles, it seemed strange to me. He had a knack for knowledge others could only shake their heads at. The obscure and the esoteric were as common to Charles as breath. “Any reason it wouldn’t be in Latin?” I asked.

Charles shrugged. He sipped his beer solicitously before adding, “It could be fraudulent.”

“A hoax,” I mused. “An odd place to find a practical joke, don’t you think?”

“If the Sulpicians considered Latin to be a holy language,” Charles suggested, “perhaps the journal’s author chose a more common language because he deemed the book’s contents unworthy of it.”

“Have you seen that before?”

Charles shook his head. “Can you leave the book with me?”

I smiled. I knew I had intrigued him, and given Charles’ bibliophilic curiosity I knew the book would be back in my hands sooner rather than later. “Take it,” I told him. “Call me when you’ve finished with it. Maybe we can meet at King’s.”

“Ah, good idea,” Charles replied. “We haven’t been there in months.”

Good things happened at King’s Bookstore. I perused a first edition of Dickens’s ‘Tale of Two Cities’ in the rare book annex. I met Paul Feig and Alice Cooper there, found a signed copy of Ginsberg’s poetry and spent an afternoon researching Olivia Maloney with the last remaining Maloney descendant living in Detroit.

![]()

Crepes and coffee were a Blackwood tradition. My wife and I attended Holy Trinity every Sunday. Amanda was Catholic, I was ambivalent, but the crepes at Le Petit Zinc were undeniably divine. We always went there after church. Our lives were so frantic just sitting down for crepes and coffee and normal human conversation felt like forbidden fruit. Our best and last conversations took place at Le Petit Zinc.

I stopped going soon after Amanda’s murder. The memories lingering there still burned my tender heart. Besides, I couldn’t get drunk on crepes and coffee. I’d traded in Le Petit Zinc for stools at P.J.’s Lager House and the Corktown Tavern. I would say Rachel saved me, but she wasn’t the one who had dragged me from the bottom of the bottle. I owed that to Olivia Maloney, and possibly Aurelius Prudentius Clemens, the Roman Christian poet who penned the Psychomachia. Olivia sang me songs on cold and sour nights, sweet and sorrowful laments that mixed with liquor and left me longing for the past. Rachel simply drove me home one night after I, having been kicked out of the Corktown Tavern, stumbled into the path of her eighty-seven Ford Tempo singing The Dead Weather’s ‘Die by the Drop.’

I don’t remember the sex, but the photographs lining her living room wall had stunned me into sobriety. There, amongst the strange and unfamiliar faces I presumed belonged to Rachel’s ancestors, were Olivia’s dark and deliberate eyes. I didn’t know her name at the time, just her face and flawless voice. I told Rachel about the dreams, about the woman who sang my lament while I slept in soiled clothes and self-pity on my bedroom floor.

Olivia had dragged me back from the brink of self-extinction. Rachel had dragged me back to Le Petit Zinc. We went there for breakfast the morning after our first encounter, and Rachel told me everything she knew about the banshee and the dullahan and the keening cry that served as death’s sad harbinger. She’d delved into Olivia Maloney’s strange and troubled past, revealing family secrets few alive remembered, and fewer still dared believe.

![]()

I met Rachel at the corner of Porter and Seventh, the memory of our first encounter still fresh in my mind.

“The Trinity School for Girls stood here,” she said. “They tore it down in the nineteen-fifties, part of their urban renewal program. During the demolition workers found human remains – a single skeleton in a kneeling position. The artifacts found with the body suggested they were Native American in nature and so professional archeologists were called in to do some digging – literally and figuratively.”

“What did they find?”

“Nobody knows for sure,” she said, “at least not anymore.”

“What do you mean?”

“Everyone associated with the dig died within the year. The bones and the artifacts disappeared. There were rumors the remains were simply left where they were, buried beneath half a century of urban evolution, but they eventually turned up in the hands of a private collector in Montreal. He donated everything to a museum in Quebec City late last year. It turns out they were Indian after all; seventeenth century.”

“What does that have to do with Olivia?”

“She attended Trinity School between eighteen fifty-eight and eighteen seventy,” Rachel explained. “She was sixteen when she died, still a child when they found her bruised and battered body hanging in a utility closet on the building’s second floor.”

She gave me a copy of the official death certificate. According to the Wayne County coroner Olivia accidentally hanged herself while playing a prank on her classmates. The unofficial records, the urban legends and local lore living and breathing in the fading remains of the old neighborhood suggested she’d died during a botched exorcism, and that the coroner simply covered up the ineptness of the priest at Holy Trinity.

“The two men were childhood friends,” Rachel explained.

I discovered something on the report that startled me. “Her mother’s maiden name was Charbonneau.”

“So?”

“So she was French?”

“French Canadian, Indian, Irish,” Rachel replied. “We’re a mixed bag, we Maloneys.”

When I told her about the journal and the empty grave she hardly seemed surprised.

“If Olivia died during a botched exorcism, those responsible for the cover-up likely buried the body elsewhere. The proof the corpse contained could potentially put them all behind bars.”

“Elmwood is a non-denominational cemetery,” I mused. “But Olivia was Catholic. Why not bury her with her fellow parishioners? At the very least, why not Mount Elliot, or Saint Anne?”

“Maybe those old boneyards were a little too close to home.”

I thought about the journal, about its author’s choice of French over Latin. The information it contained somehow linked an idol destroyed by Sulpicians in sixteen seventy to a young girl who died two centuries later.

“You’re not Catholic, are you?” I said.

Rachel looked down at her crepes. She toyed with her fork and frowned. “My family stopped attending church a long time ago.”

“How long is a long time ago?”

She looked up at me, her eyes suddenly dark. “Eighteen seventy.”

![]()

I met Charles at King’s Bookstore on West Lafayette. The four story bookstore filled an old glove factory and housed general stock while the old Otis Elevator building tucked neatly behind the former housed antiquarian books as rare and varied as Detroit’s eclectic past. We browsed the general stock first, each heading in the direction that best fed our current appetites. Charles sought books on native mythology while I wandered through local history.

Oddly enough we met beside the same book, a clothbound tome entitled The Hill of the Dead: The Great Indian Burial Mound at River Rouge. Charles held a book on Michigan archaeology and what it contained left me more than a little stunned. According to the book’s author – a professor of underwater archaeology at Michigan State – a series of stones were found in the channel between Belle Isle and Detroit’s Waterworks Park, arranged in a circle nearly forty feet below the river’s surface.

The archaeologists had been hired to survey the river’s floor between the Joseph Barry subdivision and the Grayhaven Community. Their employers had hoped to find a specific shipwreck using side-scan sonar. They found old boats and cars and a Civil War-era pier, but the stone circle was by far the most surprising discovery.

Despite everything I knew, I found it difficult not to be skeptical. “Are you telling me there’s a Stonehenge sitting at the bottom of the Detroit River?”

“I’m only telling you what I read,” he replied, handing me the book. He pulled The Hill of the Dead off the bookshelf between us and added, “It wouldn’t be the first pre-historic site found in Michigan. Burial mounds were once a common feature of Michigan’s landscape; though to this day nobody seems to know who the early mound builders were.”

He flipped through the old book’s seldom-touched pages, running a long, slender finger along the words placed there decades earlier. “When they opened the mounds, excavators found pots, beads, arrowheads, knives, chisels, and human bones. They apparently found several skeletons in kneeling positions.”

I thought about the Trinity School skeleton. It too had been found in a kneeling position.

“An archaeological survey undertaken during the twenties identified roughly six-hundred mounds throughout the state, with fifty-seven in Clinton Township alone. There were dozens in Wayne County, including several in Springwells Township. The best known of them all was the Great Mound near the juncture of the Detroit and Rouge Rivers in Delray.

“According to archaeological reports, the Great Mound measured eight-hundred feet long, five-hundred feet wide, and forty feet high. Natives from around the Great Lakes region gathered there every few years to bury tribal members and honor the bones and souls of their ancestors. The early British and French settlers knew about the mound. Among the hundreds of skeletons removed from it during the nineteenth century were the remains of several British soldiers, their bodies interred in kneeling positions as well.”

“What’s with the kneeling position, some sort of ritual burial practice?”

“It certainly denotes worship,” Charles agreed. “Who placed them there – or why – remains unknown.”

“I’ve never even heard of this mound,” I replied.

Charles pulled another book from his stack and opened to a page he had marked during his earlier exploration. The sketch depicted an earthen mound upon which a single tree grew. A farmer and his horse stood in the foreground, perhaps tilling the soil around the strange earthen blemish.

“When Detroit started growing, the once ubiquitous mounds were leveled by farmers and developers, or destroyed by relic hunters. By the late eighteen-eighties the Great Mound had been reduced to a fraction of its original size. By nineteen twenty-nine what remained was leveled.”

“I’m assuming this all ties into the journal somehow?”

Charles nodded. He handed me the two books and said, “I think it’s time for a beer.”

![]()

We had lunch and lager at P.J.’s on Michigan Avenue. While I flipped through our recent acquisitions Charles discussed the book I’d found in the empty grave at Elmwood Cemetery the week before.

“The journal is authentic,” Charles said. “The author was a Sulpician novitiate named Charbonneau.”

“Wait a minute, Charbonneau?” I pulled Olivia’s death certificate from my pocket. “Olivia’s mother was a Josephine Charbonneau.”

Charles shrugged. “It’s a common name. Our Charbonneau accompanied Casson and Galinée on their trip to the Soo. He was with them when they found the idol, but he never reached the mission at Sault Sainte Marie. According to the journal he became infatuated with a young native girl and stayed behind with her while Casson and Galinée continued on.”

“But he was a priest.”

“He was a novice,” Charles said. “Regardless, soon after Casson and Galinée left him, Charbonneau went mad.”

“Mad?”

“That’s the only way I can explain away the journal entries,” Charles replied. He opened the journal, flipping gently through the brittle pages until he found what he was looking for. “Here he says, ‘Les Indiens m’avaient mis en garde contre Adoration des Dieux Anciens’ – the Indians warned me about Worship of the Old Gods.”

“The idol Charbonneau and the Sulpicians destroyed?”

“I thought so too,” Charles replied, running his finger along the text in the book. “But here he writes, and remember his dedication, his intended audience.”

“Casson.”

“Oui, here he writes, ‘Quand vous avez abattu l’idole vous l’avez emprisonnée’– when you destroyed the idol you imprisoned her.”

“Her? Who is he talking about?”

Charles flipped through the aging journal to another page. He held the book open so I could see the text. “Here,” he underlined the text with his finger. “‘Elle n’est pas Foi’ – she is not Faith. ‘Elle se nomme Adoration des Dieux Anciens’ – She is named Worship of the Old Gods.”

Faith and worship of the old gods: the words instantly tripped the wires in my memory. I pulled the Psychomachia from my coat pocket and flipped through the small, delicate pages until I found the words I sought. “‘Fidem Veterum Cultura Deorum,’” I whispered. “Worship of the Old Gods.” I read the English translation on the adjoining page. “‘Lo, first Worship of the Old Gods ventures to match her strength against Faith’s challenge and strike at her.’”

Charles reached for and took the book from me. “I’m not familiar with this one.”

“The Psychomachia,” I said. “It describes the struggle between Christian virtues and pagan vices.”

“Like the seven deadly sins.”

“Sort of,” I replied. I debated telling him the truth, or at least what I considered it to be. I thought about my wife’s murder and my nightmarish encounter with Mother Greed at Eloise but held back. Amanda discovered the Old Gods long before I did. The discovery led to her death and ultimately my own self-destruction. I could tell Charles. He would even listen. But he would never believe it. “Look, the drinks are on me, but I do need to go.”

Charles nodded. He slid the books back across the table. “I hope I helped.”

“More than you know.”

![]()

I owned a one-bedroom condo in Rivertown. Built in eighteen ninety-nine, the refurbished building once housed the manufacturing chemists of Frederick K. Stearns. With an interior designed by Albert Kahn, the foremost industrial architect of the early twentieth century, the building had enough charm and character to make up for my lack of either.

I sat back on the couch and thought about my recent discoveries. The empty grave at Elmwood cemetery hadn’t been that surprising given everything I knew about Olivia. But the journal had been unexpected. If, as Charles claimed, the journal was authentic, it and the pipe once belonged to a Sulpician novice named Charbonneau. This same young man fell in love with a native woman named Worship of the Old Gods. If the Charbonneau on Olivia’s death certificate shared their blood, so too did Olivia. “And Rachel,” I whispered.

My stereo snapped on, ‘Rags and Bones’ by the White Stripes tearing me from my thoughts. The volume rattled the living room window and undoubtedly disturbed the neighbors. I fumbled for and found the remote, turning off the stereo. My ears and heart pounded in the ensuing silence.

The few times she’d been here, Olivia had found me in a drunken stupor. She sang my lament while I threw up or passed out on the bathroom floor. Once, only once, she had found me with a knife against my wrist. She had never seen me sober.

I had never seen her look so flawless. She stood in the loft and looked down at me with her baleful, beautiful eyes and I knew she was Faith and not the other.

I don’t remember climbing the spiral staircase, but I will never forget the comfort of her cold embrace. When her breath kissed my lips I closed my eyes and surrendered to the madness consuming me. It was madness, it had to be. I thought about the Old Gods, about Casson and Galinée and Charbonneau’s strange journal. I thought about my dead wife and I wept while Olivia took me.

![]()

I met Rachel at Detroit’s Waterworks Park the following morning. If Charbonneau’s journal held true it seemed a logical place to continue my search. I brought coffee.

“What is it you’re looking for?” Rachel asked. “Your email mentioned the journal, the Sulpician priests and someone called Worship of the Old Gods. I thought you were searching for the truth behind Olivia’s death, but I’m starting to think you’re after something stranger.”

“My wife was investigating the old Eloise Asylum when she died. After the funeral I went through her research. I thought I’d find enough to publish something posthumously. Instead I found an old photograph.”

I reached into my pocket and pulled out an old tin picture. I passed it to Rachel, who studied it closely before returning it.

“Her name’s Mother Greed,” I said. “I met her when I went to Eloise.”

“You what?” Rachel nearly spilled her coffee.

“The Psychomachia,” I whispered, quoting the verse Eloise had irrevocably etched in my brain. “‘And all the while Crimes, the brood of their Mother Greed’s black milk, like ravening wolves go prowling and leaping over the field.’”

“What are you talking about?”

“The Old Gods,” I replied. “Mother Greed’s children murdered my wife. Ever since her death I’ve been hunting down the pantheon Prudentius alluded to in his Psychomachia.”

Rachel eyed me warily. “What does any of this have to do with Olivia?”

“It has everything to do with Olivia. She was an incarnation of Faith. When the Sulpicians first arrived here in sixteen seventy they found and destroyed a stone idol venerated by local natives.”

“You think the idol was a representation of Faith?”

I nodded. “When Casson and Galinée destroyed the idol they unwittingly ensnared Faith in its stone remains.”

“Which they threw in the river,” Rachel said.

“Prudentius outlined a balance within his poetry,” I continued. “Every vice has its virtue. With Faith gone, her sister could freely influence the souls of those around her.”

“Her sister?” Rachel asked.

“Worship of the Old Gods.”

“The girl Charbonneau fell in love with,” Rachel mused. “You do realize how insane this sounds.”

I nodded, shrugged. “I’m being haunted by her ghost, her soul, her memory. I can’t explain it Rachel, but I can’t ignore it either.”

“Why come here then? What is it you think you’ll find in Waterworks Park?”

I opened the trunk of my car and pulled out the oxygen tank. “Not in the park, Rachel, in the river. I need to find the stones Casson and Galinée threw in the river. I have to find and free Faith. I have to restore the balance.”

“You’re insane,” Rachel said. “But if you want to go for a swim I won’t stop you. Just don’t expect me to be here when you get back.”

“I didn’t expect anything from you. And I don’t blame you either. I’ve been questioning my own sanity for months.”

![]()

I slipped beneath the surface. The cold water numbed but didn’t frighten me. I’d learned to dive in Georgian Bay, where the water was crisp but clear. No, the water’s coldness didn’t bother me, its opacity did. Near the surface I could still see my outstretched hands. The deeper I slid the darker and dirtier the water became until it consumed the world beyond the tip of my nose.

The Detroit Police Department routinely searched these waters for cars and corpses, and while I didn’t expect to find either I found the possibility troubling. I honestly had no idea what I would find – the strange stone circle Charles mentioned, the stone idol Casson and Galinée destroyed centuries ago, crates of bootleg booze and sunken boats, stolen cars and derelict shopping carts. They all held a place in the river’s tortured history.

In the end I found nothing. I thought about the French missionaries, about Charbonneau and Worship of the Old Gods and the strangely uncertain link that bound them all to Olivia Maloney. Charbonneau thought he’d found and fallen in love with Faith, when in fact he’d helped Casson and Galinée murder her. They had all been duped by Faith’s dark sister. According to his journal, Charbonneau married Worship of the Old Gods. Their children had children who had children who, at some point, married into the Maloney family. According to Olivia’s death certificate, her mother was a Charbonneau. Were the Old Gods alive within her blood? What about Rachel? Was she an incarnation of Prudentius’ strange pantheon as well? If the urban legends were true, Olivia died during a botched exorcism. Were the priests hoping, as Casson and Galinée were, to expunge a pagan god? If so, which one – Faith or Worship of the Old Gods?

It all seemed so absurd. Too absurd, I thought. I swam toward the surface, toward the dim, filth-filtered sunlight. I decided then that I would forget about the Psychomachia, about Olivia, Mother Greed and whatever madness murdered my wife. I’d move, leave Detroit and never come back.

When I surfaced Rachel was there, waiting for me on the shore with a smile and a helping hand. She pulled me from the water, helped me slide the tank from my back and the mask from my face.

“I thought you were leaving,” I said.

My copy of Prudentius lay open on the break wall, its pages flittering in the breeze.

Rachel followed my gaze and her smile broadened. She reached down and picked the book back up. “We are born within your kind, Daniel. For all your research you missed that small but vital point didn’t you?”

“What are you talking about?”

Her gaze held mine. “We are born within you.”

“Rachel?” I whispered, suddenly uncertain.

She slowly shook her head. “No, I’m not,” she breathed, and I didn’t understand until she began reciting Prudentius. “‘Why in the hour of birth we embrace the whole of man, his frame still warm from his mother, and extend the strength of our power through the body of our newborn child, we are lords and masters all within the tender bones.’”.

Jason Rolfe writes for fun and (very little) profit. His work has recently appeared (or will be appearing) in Sein und Werden, The Ironic Fantastic, miNatura, Pure Slush, Flash Gumbo, Black Scat Review, Apocrypha and Abstraction, and Cease, Cows.

Jason Rolfe writes for fun and (very little) profit. His work has recently appeared (or will be appearing) in Sein und Werden, The Ironic Fantastic, miNatura, Pure Slush, Flash Gumbo, Black Scat Review, Apocrypha and Abstraction, and Cease, Cows.

If you enjoyed this story, let Jason know know by commenting — and please use the Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus buttons below to spread the word.

Story illustration by Peter Szmer.

Thanks a bunch Tim. I’m really glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

This is a great story. I liked the mix of fake and real texts throughout the story. The dialogue was great as well, which can be unfortunately uncommon in Lovecraftian stories.

LikeLike

This is so similar to stuff I write, I love it. I’ve been chewing on an idea of a pyramid at the bottom of Lake Michigan. I’ve also been working on my own Cryptotheology and mythos books. I love the idea of lost books written by the first Spanish and French explorers of the interior, though I center my stuff on Chicago.

LikeLike

Thanks very much, Mark! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

That ending definitely strikes the right note. A very enjoyable and memorable tale.

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind comments, Carl. More an ‘homage’ than a true Lovecraftian tale, in my opinion. While I didn’t intend to write a Lovecraftian tale, I did want to pay my respects to that particular author (without simply creating a pastiche), so your thoughts are definitely appreciated!

LikeLike

Er… would that be a ‘Lovecraftian’ or a ‘weird’ tale?

Not that this kind of labelling matters much, I suppose; K. Ed. Wagner’s ‘Sticks’ had little more than an oblique reference to “Yught-Sut-Hyrath”. The important is that it works.

LikeLike

Not your run-of-the-mill tale that screams pastiche. And a very human protagonist. Thumbs up.

LikeLike

Thanks Mark, John, and Destiny! Mark, I grew up across the river in Windsor, Ontario. I included a few of my favourite Motor City haunts in this story. Again, thanks everyone. I really do appreciate the feedback!

LikeLike

Very good tale. I loved it.

LikeLike

A well-woven tale…Not a common thread to find in a Lovecraftian short story…Very original…

LikeLike

Ah, I am an Irish/Native American from Sparta, MI. I lived about a mile from the Rogue River growing up. I think I am going to share this great story with my family in Detroit. Sorrow filled, moneyless Detroit. Hmmm.

LikeLike

Thanks! I really appreciate the feedback. You know, I fought with that ending, and although I won, I still felt a bit uncertain. I’m thrilled that you liked it!

LikeLike

what a thrilling read, thank you…i loved the ending

LikeLike

Thanks Peter, for the artwork accompanying this story!

LikeLike