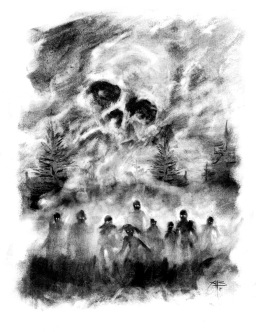

Art by Adam Baker – http://www.thinkbaker.com – click to enlarge

My old man used to call it ‘rain blush.’ That time of year when the world teeters on the brink of winter, where the air takes on such an icy crispness that it seems almost brittle, and crackles with an electricity that hints at the possibility of snow. Where spectral tongues of morning mist leave films of cold condensation on pavements and hoods of cars. It used to scare me, somehow, in ways I could never fully grasp. It made me feel small, like I was made of matchsticks.

Of course, I was small, barely seven years old the day my father first took me aside, pointed up at the endless white expanse of winter cloud, and told me about the rain blush. And like all kids, I didn’t understand the extent of my insignificance, Of the length and breadth of life beyond the narrow clutch of streets I walked, or ran, or cycled down, and the people who filled them. The world began when I opened my eyes in the morning, and ended again when I closed them at night. And nothing of any importance existed beyond my field of vision.

So when the rain blush would come, when that terrible static charge would fill the air, it seemed as though the end of the world was coming with it. Nature, nurturing and benevolent, turned hostile, with a cold fury barely held in check by the paper-thin skin of reality. Yes, it used to scare me, and I make no bones about it.

But it wasn’t just the weather. The rain blush took things. It would come on without warning, and you’d wake to the light patter of rainfall, and the sharp smell of the sea. And when it disappeared, things would disappear with it.

Sometimes, people disappeared with it.

![]()

When I was eight, it took my neighbour’s dog.

When I was twelve, it took a little girl called Sally Patterson. The manhunt lasted nearly a year, and turned up nothing but a single small ballet shoe, wedged up high in the branches of a tree, as though she had been whisked into the sky with the last of the rain blush mists.

The next few years were mild. Again and again, autumn slipped seamlessly into winter, and I saw nothing, and felt nothing. It returned when I was eighteen. I’d left home by then, and I was working the railway lines with my dad. The mists were thick as bonfire smoke, and heavy with brine. They made the sleepers shiny and slick. The day they lifted, I learned the rain blush had taken another passenger. A boy this time, a local lad I’d seen in passing as I walked north to the rail yard, and he walked south to school.

This time, the police found more than a shoe. Whatever rough beast stalked the town under the cover of the fog had done the boy’s family the courtesy of leaving his backpack, his jacket, and his medic alert bracelet. It had all been left on the train tracks. It’d been found by a friend of ours, John Garvey, a taciturn twenty year rail man with a face built for a perpetual scowl. When he found the boy’s things, that granite face had crumpled like paper, and he’d never been seen on the rail yards again. The bracelet had borne his son’s name.

When I was little, I’d asked my dad, why rain blush? He’d shrugged his shoulders and told me he’d picked up the term from my granddad, who’d never seen fit to explain it to him. Best Dad could figure, it was because a rain blush was false, like a painted face. It wasn’t a real winter. It was just the shadow of one. Apparently, Granddad used to say that the longer the rain blush, the longer and harsher the winter which followed it.

The rain blush of my twenty fifth year lasted almost a month. And after a seven year absence, it came back hungry.

![]()

All they ever found were keepsakes. A bicycle, upturned on a country lane, its front wheel festooned with streamers, still spinning lazily, turning against the wind. A baseball cap, bright red, and adorned with childish graffiti and signatures of friends. A hearing aid. By the time the mists rolled back into the sky, five were missing, and the town was in the grip of a paranoia more contagious than any winter flu, and infinitely harder to treat. It poisoned every interaction. There was less laughter and fewer smiles, and those that were shared were briefer and less genuine. And a ubiquitous question hung in the air like a bad smell.

“Who are you, really?”

The police instituted a curfew after the third disappearance. For all the good it did, they may as well have marched against the turning of the Earth. The local chief constable wilted under a barrage of criticism and resigned without protest. My mum even started walking my fourteen year old sister to school, much to her horror.

Two weeks after the rain blush had evaporated, I came down to breakfast serenaded by shouts of joy from the kitchen. I opened the door to see Mum waving a paper in dad’s face.

“They’ve got him! Evil bloody bastard, they’ve got him!”

It was the only time I can remember Mum swearing in my presence. She had tears in her eyes, and held the paper crumpled in trembling fists. She’d babysat for John Garvey’s boy when he was little, and counted John’s wife among her oldest friends. Even my sister’s studied apathy was no match for the momentousness of the news. I gave Mum a hug, and she put her head on my shoulder.

“They can’t have,” my father whispered.

It didn’t register at the time, the strangeness of that remark.

![]()

The next day’s paper carried a photograph, but really, all anyone in town would have needed was a name.

Bible Jack. A hollow-eyed, emaciated car crash of a man, homeless as often as not, given to impromptu sermons on the evils of whatever happened to be in his field of vision. Every town has a Bible Jack or two skulking around. Like all the best jokes, he was tragic at heart. But whatever sympathy he may have enjoyed curdled into loathing the moment the first edition hit the doormats. From his sly features, to the tangled chaos of his beard, he was a man it was easy to believe the worst of. Apparently, he’d been seen in the woods the day the police found the Jackson girl’s bicycle.

While being transported to, ironically, a more secure facility, an enraged mob led by none other than John Garvey forced the police van to a halt. With crowbars and fists, they wrenched the doors off their hinges, and with those same implements they unleashed all the pent up fears and frustrations of the town on his helpless form.

And that was the end of that.

![]()

That year, I spent Christmas with my parents.

Exercising paternal prerogative, dad carved the turkey in front of us, piling our plates with mountains of steaming slices and sausages bursting through their skins. After dinner we played cards. Dad cheated, but mum won anyway, and when time came for bed I walked upstairs to my old room, savouring the familiarity of every footstep. The room hadn’t changed a bit. It was still bedecked with posters of snarling punk bands, and piles of ancient comics and dog-eared old notebooks filled with superheroes of my own design and half-finished short stories lay in every corner. It felt like home should always feel, like I’d never even been away.

The house was a late Victorian build, and draughty as an old Church. The wind was ferocious that night, and with every gust the floorboards creaked and the windows rattled and the hinge on my bedroom door, which never shut properly anyway, squealed in protest. After about three hours of tossing and turning I’d had enough. I got dressed and went downstairs and into my dad’s tool shed. I clicked on the light. The shed was my dad’s sanctuary, and it was organised with military precision. The tool box was resting against the wall. I dragged it away and opened it, looking for a screwdriver, or maybe a can of oil, and when I did, a piece of skirting fell into the vacated space.

Behind it was a single, red ballet shoe.

![]()

“It’s not what you think.”

I turned and stared at the stranger in the doorway. He seemed to have aged ten years since dinner. I held the red shoe up to him hesitantly, like an offering.

“What is this?” I whispered. “It’s Sally Patterson’s other shoe. Dad, what are you doing with it?”

Wordlessly, he moved past me and reached behind the exposed hollow in the skirting. He pulled out another identical shoe, and then another, and another.

“I’ve got about a dozen behind here. They just keep turning up.”

“Dad…I’m sorry, I don’t…”

“I know you don’t,” he interrupted quietly, “I don’t either.”

“Why have you got all these?”

“I think it might be easier if I show you. Come with me.”

I followed my father to the car and together we drove towards the woods. Dawn was breaking, a reddish haze haloing the chimney pots and the tree tops. We drove deep into the forest. After a few minutes, Dad got out of the car and beckoned me to follow him.

“They like it here,” Dad said. “It’s…what’s the word? Tranquil. Yeah, I reckon that’s why they come here. You got to be very quiet.”

“Who likes it here?” I asked.

“The kids,” he replied, as though that answered everything.

We walked for a few minutes until we came to a clearing. As the morning sun bled through the trees, I saw them, creeping over the foliage, moving with a lightness that was both graceful and unnatural. A small girl with ballet pumps and a white satin dress. A boy with a thin metal bracelet hanging off his wrist. Another with a red baseball cap covered in marks, with a crooked smile and a birthmark on the back of his hand. They wandered through the forest, unaware of not only myself but seemingly of each other. As I looked closer, I saw that the boundaries of their slight forms were somehow hazy and indistinct, like I was seeing them through bad glass. The forest was silent as a crypt, and I’d never known the air to be so still.

“You can see them?” Dad whispered. Out the corner of my eye I could see him studying me, gauging my reaction. I opened my mouth to speak, but nothing happened. Taking that for assent, he broke into a broad grin. He straightened, as though relieved of a heavy load.

“Thank Christ,” he whispered. “Most people can’t. I took John down here, after his little boy was…y’know. He couldn’t see ’em at all. Hasn’t really spoken to me since.”

“What are they?”

“I don’t know.”

“Are they…” the word ‘Ghosts’ stuck in my throat.

“I don’t know.”

“How did you…?”

“I don’t know,” he turned to me, “I’m sorry, son. I ain’t got no answers.”

“How long has this been happening?” I asked anyway.

“Granddad first showed me.” Dad said “For all I know his dad may have shown him. Maybe seeing it runs in the family? I don’t know.”

“And you’ve been coming here ever since?”

“Someone has to,” Dad said, “I think we owe ’em that much. Sometimes, things just sort of turn up. Like the shoes. I keep ‘em if I find ‘em cause, well…better I find ‘em than their parents, yeah?”

“What are they? The shoes, I mean.”

My father shrugged. “Echoes, I reckon.”

I nodded as though I understood.

“What happened to them?”

His answer was a mere three words, and seemed to explain everything and nothing at the same time.

“The rain blush.”

We stood in silence for a few minutes, as I tried to stifle the terrible pounding of my heart. My skin was rough, and strange with goose bumps and each breath was an effort, like I was breathing through a handkerchief. After a few minutes, Dad put his hand on my shoulder and motioned for us to leave. I took a step backward and stepped on a twig. It cracked like a pistol shot and the children’s heads snapped towards us with animal speed. Their eyes were white, like spider’s eggs, and not for seeing anymore. And they smiled, privy to a joke I couldn’t see, hear, or understand. I’ll never forget the sight for as long as I live.

![]()

That was fifteen years ago. I’m married now, with children of my own. Every few years, the rain blush comes and I walk around with my heart thumping in my throat. I used to talk to my wife about leaving, but the conversations just ended in arguments. She has roots here, and couldn’t leave, even if she wanted to. And when I took her to the forest on a pretext, she saw nothing.

Besides, it hardly matters anymore. In recent years, the rain blush has become a global phenomenon, baffling meteorologists and ministers alike. It descends like a shroud, covering the whole world, sometimes for only a few days, sometimes for longer. Global Warming, the television says. Only my father and I know different.

I used to believe in God. Now I believe only in an afterlife. I see it in the forest, one world spilling into another. My friends make fun of me, how I worry. They call me a helicopter parent, always hovering. And my kids certainly resent my constant interference. I can see them now, playing in the garden, and I don’t dare turn my back, even for a second. Because the skies are whitening, the wind is turning cold and cruel, and the air is rich with the tang of the sea. The rain blush is come.

I can never keep them safe.

Neil Murrell is a longtime H.P. Lovecraft fan from Essex, England. This is his first short story. His other passions include cooking, card tricks, writing music, and playing with matches. He is currently working on his first novel.

Neil Murrell is a longtime H.P. Lovecraft fan from Essex, England. This is his first short story. His other passions include cooking, card tricks, writing music, and playing with matches. He is currently working on his first novel.

If you enjoyed this story, let Neil know know by commenting — and please use the Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus buttons below to spread the word.

Story illustration by Adam Baker.

Rivetting Neil, let the flow become a flood. – Very good luck with the developing novel.

LikeLike

Fantastic story, i am shocked this is your first published work,you write with a skill and intuition far beyond your short years. You have real talent Neil, a very rare thing. I am genuinely looking forward to reading more of your work

LikeLike

I love this story, it’s very atmospheric with a pervading sense of dread. Well done sir!

LikeLike

Very well done.

LikeLike

Another new talent to watch! Keep at it, because if THIS story is the start, you’re going to go places!

LikeLike

Poetic and ominous descriptions, smooth twists and turns in the narrative. I love discovering new authors.

This being your first short story, you have a promising career in publishing, indeed. I’m excited to see more.

LikeLike

Enjoyed your story very much; great description and it went in a direction I didn’t expect.

LikeLike

This is an excellently creepy read!

LikeLike

Excellent start. I enjoyed it greatly. Keep writing.

LikeLike

Wonderfully creepy, superbly written, an excellently realised tale!

LikeLike

Utterly atmospheric! Way off the gauge of the weird barometer. i succumbed to this story; can death be far behind?

LikeLike

Fantastic, spine tingling stuff!

LikeLike

A brilliant writing Neil, I’ve shared this on my Facebook and had some great feedback from it too. Excited to see what else you have in store for 2015.

LikeLike

great story, had to share it after reading it, can’t wait for more

LikeLike

Great story, Neil. I think this is my favourite of yours.

LikeLike

Thanks very much guys. I’m really glad you liked it 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Neil, I have a message from the Westcliff author Harold Salkin who asked me to pass on the following message as he does not use the internet. (at 86 he’s done really well learning how to use a computer to write his second book!) ‘ Dear Neil, I read your story, Rain Blush, with interest and great pleasure. You write well: better than me. I sometimes reach the top standard, but you do it nearly all the time. Best wishes from Harold Salkin and give my regards to your Mum and Dad.’

LikeLike

Same here, Neil, excellent first story. I hope to hear more of this town!

LikeLike

Nice, I would like to read more.

LikeLike

Good first story, Neil. Good place to gain some readers as well.

LikeLike