(By Cody Lakin, author of The Family Condition and The Aching Plane.)

“That intersection of the real and otherworldly, the insignificant and the cosmic, the mundane and the horrific, the literary and the genre, is why I fell in love with Langan’s work in the first place, and is why I continue to love his work”

After reading one of my horror novels, a friend and fellow writer once said something to me along the lines of, “You’re actually pretty good at writing the love story stuff. Maybe one day you’ll try that without the horror part?”

I don’t remember if I said this or merely thought it, but I remember exactly the response that came to mind: “But why would I ever do that?”

My first encounter with a book by John Langan was the beginning of what I have no doubt will be a lifelong love affair. Wrapped in his exquisite sense of voice and style was an emotional honesty I can only describe as authentic, and the writing itself scratched an itch in my brain that I don’t always expect to be scratched in genre fiction. When I first read The Fisherman, I remember thinking, “This could be a serious literary classic I’m reading, but it happens to be a cosmic horror novel—and with monsters!”

When it comes to my personal tastes, that’s an uncommon and particularly wondrous high: one of those items on the menu at the nice restaurant you’re unsure of but decide to give a try, and a week later you still can’t get the taste out of your mind. This encapsulates an amalgamation of things I’m ever hungry for in fiction, and which is to be cherished when found. Shirley Jackson, Peter Straub, Mariana Enriquez, and Dan Simmons are just a small handful of names that come to mind, who’ve both satisfied and deepened that hunger in me.

And as I read John Langan’s newest collection, Lost in the Dark and Other Excursions, a certain phrase kept haunting my thoughts:

Horror changes the conversation.

We’ll come back to that.

The first thing that comes to mind in facing the challenge of describing this collection is how playful it is. There are stories within stories, unique approaches to frame narratives, as well as experimentation with the entire delivery method, so to speak, of the story. “My Father, Dr. Frankenstein” is a story told in endnotes. “Madame Painte: For Sale” weaponizes the second-person point of view in such a way that, when the story decides it’s time, it essentially punches you in the face, to both humorous and genuinely chilling effect. The title story, “Lost in the Dark,” isn’t merely written like a record or documentary of real events, it actually feels that real, too, as it circles around empty spaces both literal and metaphorical. That story, as well as “Haak,” another of my favorites, showcases Langan’s singular gift for myth making, which is to say, his understanding—and ability to portray—how the past is a story we tell, and as long as that story exists in the minds of people and is shared among them, it is a living thing, possibly a dangerous thing, and it is shaped by the tellers, by the context and culture they live in, and by everything that comes and goes with the passing of time.

When it comes to reviewing a collection of short stories, there’s always the temptation to sort of list the stories and what each one is about, just as, in reviewing novels, there’s also the option to summarize the plot. I mention this for two reasons. One: to say that this is something I avoid when writing reviews, mostly because I enjoy reading book reviews as much as writing them (and when I read book reviews, I’m there for the reviewer’s thought and feelings; if I want a plot description, I’ll read the blurb/summary). And two: I mention this because it occurs to me, a surface-level summary of the plot of a John Langan story is almost always woefully insufficient. To say “Natalya, Queen of the Hungry Dogs” is a ghost story, or one level deeper, that it’s a story about what lengths a person might go to for someone they love—a friend, or a sister—to say even that is to leave out so much of what the story has to offer. Langan’s ability, for example, to convince you of the flesh-and-blood reality of entire characters in a mere paragraph or two, sometimes less. Or, how much emotion is folded beneath and between the words, rarely outright pointed to but nonetheless palpable.

That Langan has so much fun with form and structure is pure gravy, though even to say this feels like it discounts the importance of the layers of Langan’s storytelling. You won’t find anything there “just because,” or find experimentation for experimentation’s sake, in these pages. And perhaps that’s a separate point, but it’s another reason why I love the work of John Langan. When a writer is compelled to push themselves, to press up against their limitations or to tread new ground so as to avoid stagnancy, it might be easy to fall into the trap of “how,” but in the process to forget “why.” It might be easy, I mean, to try on a new voice, or to experiment with a form, trope, or even a whole genre, just to do so, forgetting or ignoring the more important considerations of why one is doing those things. John Langan never forgets the why. If he were the owner of a weird fine-dining experience, you could trust that the meals aren’t being deconstructed just to be fancy, no. Each course wouldn’t merely be deconstructed, it’d be vivisected and then dissected, with each deconstructed aspect presented with context and with purpose.

I love literary fiction and I love horror, and their intersection is where my favorite fiction tends to live. Horror, when approached as though it were literary fiction, tends to leave the deepest grooves in my brain. If there’s a common theme among the books I love most under the umbrellas of literary fiction and horror fiction, it might be their relationship to interiority. No description is ever just a description, no detail is ever just a detail, and nothing supernatural or uncanny is ever there just to be there, it is so often an extension of the perceiver, part of the statement or conversation about the human experience and condition, and it’s all in service of the bigger picture. The inner and outer worlds blend and blur, creating space for unexpected experiences and feelings to rise. That’s a long way of me trying to say, the characters and the worlds in this collection feel truly lived-in. More than trying to scare or unsettle you, these stories set out to convince you, and that’s exactly what they do.

At the onset, the characters in most of these stories are convincing enough in their lives and their struggles, their stories would be compelling on their initial trajectories, if only thanks to the masterful storyteller. But horror changes the conversation, and this is a John Langan book we’re reading. There’s a crossroads waiting, at some point ahead; or maybe you’ve already passed it and didn’t realize until it was too late. The story of someone going to visit their dying friend becomes a conversation about more than just mortality when you introduce a liminal realm of trapped ghosts beyond the edge of life. A simple tale of recalling a strange moment in time and a senseless loss, with the mere suggestion of the otherworldly, brushes up against the cosmic sense of one’s own insignificance. The world is not what it seems. It has cracks, and sometimes it opens up enough for us to fall into—or for something else to fall through.

That intersection of the real and otherworldly, the insignificant and the cosmic, the mundane and the horrific, the literary and the genre, is why I fell in love with Langan’s work in the first place, and is why I continue to love his work.

Finally, if my relationship to the horror genre can be likened to an actual relationship, one of my favorite things I’ve ever heard about the nature of a healthy long-term relationship is this: You have to fall in love with your partner over and over again. That means the relationship as you once knew it will end, and so you will have to start it anew; and eventually that one as you know it will end, and you will have to start it anew. This is daunting, of course, but it’s also exciting. The chance to fall in love multiple times, and with the same person.

My relationship to horror has been like this. And though it’s only been a few years since I first discovered the horror fiction of John Langan, I can say his work renews and redefines my love of horror again and again. Lost in the Dark and Other Excursions is clearly the work of a writer who refuses to stagnate, who reexamines and reevaluates himself and then pushes himself, willing to grow and evolve.

I felt deeply invigorated while I read this book—both as a writer and a reader. It echoes what came before while promising what is to come, in the genre of horror and in the horror of John Langan.

(By Cody Lakin, author of The Family Condition and The Aching Plane.)

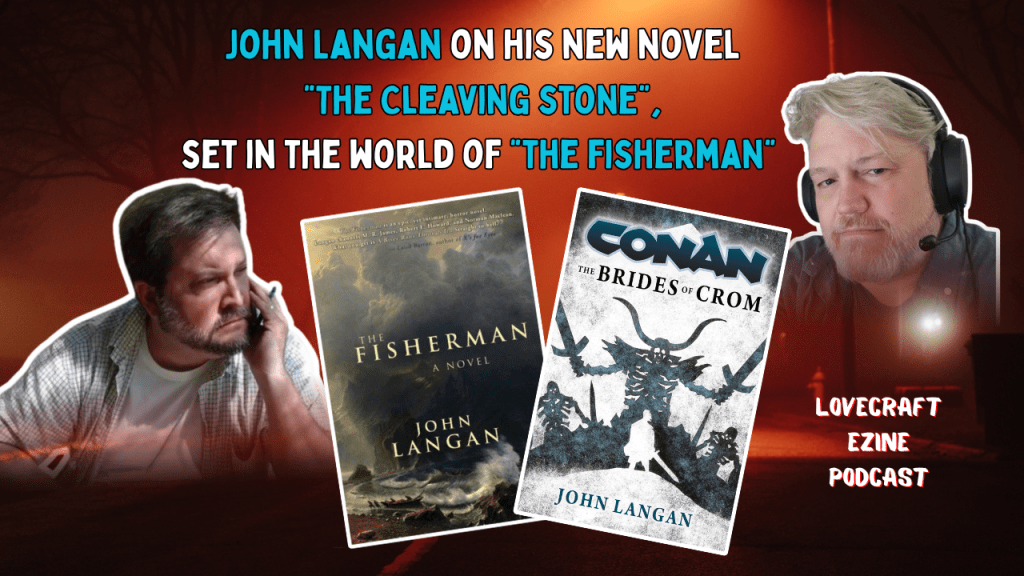

Listen to our recent interview with John Langan about his upcoming novel The Cleaving Stone! It’s on YouTube, Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Discover more from The Lovecraft eZine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.