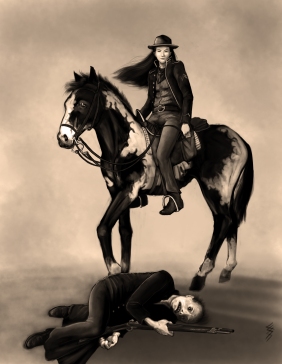

Art by Christoph Schulz: http://csschulz.deviantart.com/gallery – click to enlarge

Art by Christoph Schulz: http://csschulz.deviantart.com/gallery – click to enlarge

Fussy gave a surprised cough as the bullet tore through her neck. She managed another few strides before pitching forward in a tangle of hooves. I hurled myself from the saddle before she could crush my leg, the rocky Texas hardpan scraping my hands raw. Fussy was on her side, painting the dirt red as she struggled to rise. I crawled the few feet to her, close enough to run a hand through her mane. It came away sticky with blood. Fussy choked, the look she gave me equal parts pain and reproach.

The knowledge of what I had to do was bitter as a misspent youth, but Fussy had been a fine horse, and only cowards don’t take care of their own. My Colt’s report was distant, muffled as if carried along the buzzing string of one of the tin can telephones Simon and I used to make from Ma’s empty bean tins.

Fussy jerked, and fell still.

My Sharp’s carbine poked from its saddle holster like an accusatory finger. In the clenched fistful of seconds it took my unknown assailant to reload, I’d snaked the rifle from its case and slipped a percussion cap and bullet into the breach. I saw the glitter of muzzle flash from some scrubby bushes on a ridge a few hundred yards distant.

The shot kicked up a spray of dirt to my right, but I didn’t duck. Either the shooter had me dead-to-rights or he didn’t, and I was betting on the latter.

I could tell from the way he hadn’t repositioned after firing he wasn’t an experienced sniper. If he’d been a Comanchero or road agent it would’ve likely been me watering the hungry ground rather than poor, old Fussy–though maybe not if he saw the woman under all the leather and trail dust. Might be he wanted me alive. If so, he’d be sore disappointed. I’d seen enough at the battle of Tabasco to know I’d rather die than be taken. The derringer in my ankle holster had two bullets–the first for him who tried, and the second for me, just in case.

My shot came fast on the heels of his next one, close as the beats of a drum roll. His bullet scraped a long divot in the dirt near my boot. Mine went right where I’d sent it.

This was the most dangerous part–not knowing whether you’d plugged your man or he was laying low. I put another shot into the scrub. Nothing. Either he was dead, or a damn sight cooler than I’d given him credit for. I reloaded, then eased onto my battered knees, carbine braced against my shoulder.

After a few long breaths, I knelt to pat Fussy’s cooling muzzle, my voice thick as molasses. “Rest easy, girl. I got him.”

I approached the ridge cautiously. Gunfights were rare, even in my line of work, but usually when someone started flinging lead my way I had a pretty good idea why. It couldn’t have been a rival bounty hunter–there was no reward for the man I was after. That I’d run into a shooter this far south of nowhere just seemed to be another hand in the run of bad cards I’d been dealt since I left Slaughter Ridge.

I smelled the body long before I saw it. The breeze brought the expected reek of bourbon-laced sweat, along with a brackish smell, like the Houston waterfront on a hot day. The shooter was doubled over. When I nudged him with my carbine he slumped to the side, dead. His eyes were large and glassy, his nose little more than two slits. Blood leaked from the corner of his mouth, which gaped wider than it had any right to. He was dressed in preacher’s robes, though they were purple instead of vulture-black, and closed at the throat by a gold choker.

He wasn’t carrying much apart from the robes and the rifle: three empty canteens, bullets, percussion caps, and a twist of jerky. His skin was grimy as a cowpuncher fresh from a three-month drive. Up close he smelled like he’d been dead for five days rather than five minutes. I undid the choker. It had the heft of solid gold, and was wrought to resemble a circle of crashing waves. When I turned it in the light, the image shifted, breakers transforming into a herd of running horses, their manes etched in arcs of sea foam, the pounding surf captured in the delicate curve of their necks.

I’m usually not one for jewelry, but I was still choked up over Fussy, and the necklace seemed like a mighty fine way to remember her. Besides, it looked damn fetching when I regarded myself in the polished blade of my Bowie. Even so, I cinched my scarf up to hide it. Gold might be fine for cotillions and whatnot, but nothing good ever came from flashing it out here.

The remains of a greasy campfire told me the shooter had been here at least a day, probably more judging from the scorched bones and refuse amidst the ashes. There wasn’t much else. This fellow might have been here a spell, but it didn’t look like he’d planned to stay much longer.

A soft whicker led me to a pinto mare roped to a stand of desert willow. The white patches on her coat were the color of bleached bone, and I could see her ribs clear as if I’d skinned her. I clenched my jaw against the expected upswell of emotion–Fussy had been bad-tempered even at the best of times, but she’d never let me down. This pitiful thing looked like she could barely carry a rider. Still, it would be a long walk to La Puerta, and I didn’t fancy hauling my own gear.

A pail of water did the mare a world of good. It was my last, but she needed it more than me. The mare snuffled at the bucket, almost biting my fingers in her haste. I collected my gear and cinched the saddle around the pinto’s chest. My quick tightening of the straps would’ve earned a glare from Fussy, but the mare didn’t even glance up from her water.

I left Fussy and the shooter for the coyotes, just like I hoped someone would have the courtesy to do for me one day. Never fancied dirt much, and burning always seemed like a waste of good tinder. Nature takes care of her own well enough.

![]()

From a distance, La Puerta looked just like every other boomtown–a mess of tents and clapboard shacks clustered around a few semi-permanent buildings. I’d seen plenty of the same farther west, sprouting like mushrooms around ore veins, except as far as I knew, there weren’t gold-bearing hills within a hundred miles of here. The town only got stranger when Thirsty–that’s what I’d taken to calling her–and I ambled in. In my experience, towns like this tended to be quite lively at night, but the rutted dirt road that served as La Puerta’s only thoroughfare was almost empty, despite it being early evening.

I led Thirsty past a pale Oriental in a coat of green and gold brocade unloading what I was pretty damn sure were bodies from a covered wagon. A snake oil salesman had staked a claim in one of the empty plots, his brightly painted wagon advertising cures for everything from rheumatism to the runs. The man himself stood out front, arms crossed and top hat tipped forward over his brow. The tips of his waxed moustache twitched as he watched us pass, his glare sharp enough to draw blood.

A group of mestizos squatted out front of half-circle of tents. They carried themselves like presidiales–most likely the remnants of some Mexican unit left high and dry by Guadalupe-Hidalgo. I hoped my scout jacket was too tattered and dusty for them to notice the corporal’s stripes. They were passing around a bottle of tequila, watching an old woman with a face like weathered hardpan sketch strange symbols in the dirt. I thought I recognized a few signs from Ma’s books, but wasn’t curious enough to risk being gunned down just to have a look.

The town’s saloon was a drab affair, its false front listing like a sleepy drunk. A vulture and a crow perched on the worn hitching post out front. When I approached, they looked up like I was interrupting something. Thirsty whinnied and the birds took flight with an air of wounded dignity. I had to tug at the bridle to get her hitched up proper, as she’d already plunged face first into the trough. Fussy would’ve turned up her nose at the musty water, but the pinto almost bathed in the stuff. It must have been the darkness, but I could’ve sworn the dark blotches on her coat were growing.

A dozen rough tables crowded the room, although only one was occupied, the single patron little more than a shadow in the dim light of the saloon’s handful of gas lamps. The whole place smelled of cedar and vomit–the first normal things I’d encountered in La Puerta. The proprietor hunched behind the bar, scribbling in a leather-bound book. He was a skeleton of a man, rawboned and pinched, with thinning hair slicked back over a scalp shiny with sweat.

Usually, even men who wouldn’t flinch from slitting throats by moonlight stood up when they realized I was a woman, but neither the barkeep nor his sole customer so much as looked at me. I had to slap down a silver dollar to break the proprietor from his writing.

“What the hell you want?” His speech was flavored with hints of German, maybe Dutch.

I eyed the row of bottles lined up before the greasy mirror. “A bourbon, and a few minutes of your time.”

“We’re closed.”

I added another two dollars to the pile. “I’m looking for–”

He didn’t even blink. “Awful late to be looking for players. Don’t you know what goddamn day it is?”

The only thing I hate more than being shot at is being interrupted. I lunged across the bar and hauled the barkeep up by the collar of his shirt. Most folks don’t think I have it in me to lift a man one-handed–on account of me being so sickly looking, and a woman to boot–but I got a dose of Ma’s terrible strength, more than enough to rattle the teeth of any skinny jackass who thought he could push me around.

A chair scraped as the shadow pushed away from his table.

“I wouldn’t.” I drew my Colt and the sounds stopped. “I’m looking for a man. He’s a little taller than me, dark hair, darker eyes, thin as a rail, likes the sound of his own voice. He might go by the name Simon, or maybe Szymon, or Shim’on. I know he’s in La Puerta.”

“You can’t hurt me.” The barkeep’s gap-toothed sneer wilted what little patience I had left. “Not this close to midnight. It’s against the rules of the game.”

“I ain’t playing no damn game.” I knocked his head against the wall, hard. His look of wounded disbelief was enough to bring a smile to my face. “Now, let’s try this again. Simon: you know him?”

He nodded.

“Where is he?”

“Old temple, out near the river.”

I set the man down, smoothing the wrinkles from his shirt, nice and civil.

The barkeep squinted at my throat, the corners of his mouth twisting into a furious scowl. In the mirror I saw my scarf had slipped to reveal a thin crescent of gold.

He hissed something in German–I’m sure it was German. The man behind me shifted, his boots clattering strangely on the floorboards. I shot wide, hoping to startle him, but he came on like a stampede.

His eyes were points of red in the gloom, and the wan lantern light glittered off what looked like–but couldn’t possibly be–horns on his forehead. I put two bullets into him, but might as well have been shooting at fire for all the good it did. He grabbed my wrist, his grip hot as a brand. I could smell my jacket scorching, curls of smoke rising through his clenched fingers. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t terrified, but I’d been in enough brawls that my instincts were there to catch me. I aimed a knee at his groin, then grimaced when I saw his legs were furred, the knees crooked backwards like a dog’s, his ankles tapering to a pair of cloven hooves, shiny and black as a preacher’s Sunday best.

I had just enough time to cotton I might be tussling with Lucifer himself before a boom and a flash set us both sprawling.

“Just what in the Sam Hill is–Fran?” The man who stood in the doorway was tall and long-limbed, with a thin blade of a nose, and deep-set eyes the dry brown color of cured wood. He wore a leather duster over his clothes, the silver star of a Texas Ranger pinned to his vest. In his hands were the twin Colts I remembered from when he was my captain.

The devil backed away with a snarl, crouching with the German in the shadow of the bar.

I stood and tipped my hat. When in doubt, act tough.

“Rip. Much obliged.” I tried not to glance at the devil behind the bar. I’d seen plenty of strange things in my life, though usually not so many at once.

“Fran, what are you doing here?”

I regarded him carefully. John Ford had been a good captain. Upright and uncompromising, he’d earned the nickname Rip for his habit of adding “rest in peace” after each name on the casualty lists. He held no prejudice toward anyone with a steady hand, a nose for the trail, and steel in their spine, but I’d also seen him order the massacre of a Comanchero village without so much as twitching an eyelash. He knew me well enough to suss out any lies, but I didn’t fancy telling him about Simon, especially if we were after the same man.

“Kill her!” the German shrieked from beside his devil. “It’s Zakariah’s damn wasserpferd!”

“Easy, Johann.” Rip’s voice was calm, although I couldn’t help but notice he hadn’t holstered his pistols. “This here’s Corporal Drusilla Marsh, I served with her in the war–best damn scout I ever saw, but no kelpie.”

“She wears the collar!”

Rip regarded my neck with a raised eyebrow.

I looked around the room. Rip was blocking the door, and I didn’t want to take my chances with Johann’s pet devil, but the saloon’s clapboard walls didn’t look too sturdy. All I needed was a good head of steam.

“The man who wore this killed my horse,” I said at last. “Would’ve done for me too if I hadn’t gotten him first.”

Rip lowered his pistols and smiled. “You did a damn fine thing if you put old Zachariah down. Hell, Johann, we might even pull this off.”

I grinned back, mostly to hide the fact I was fixing to bolt. Old friend or not, I’d had just about enough of La Puerta. I knew where Simon was, although not what he’d gotten himself into.

“We could use the wasserpferd,” Johann said.

“You should hand the necklace over, Fran.” Rip raised a calming hand. “For your own good.”

“Seems to me it’s mine by right.”

“Where’s the horse?” Rip asked.

I swallowed my surprise. I’d left Thirsty hitched up out front. Rip would’ve had to saunter right past her on the way in. “She was half-dead when I found her, wouldn’t have made it five miles. I let her go.”

“You left a sick animal to die all on its lonesome? Now I’ve heard everything.” Rip holstered a pistol, but just one. He smiled at Johann. “We used to call her Fran back in the scouts–on account of Saint Francis. I seen her turn up her nose at plenty of dying men, but never a critter. Never.”

“Just what the hell is going on here?” I needed answers, not questions. “There’s a mess of presidiales out front, a barker with no patter, and some Mandarin undertaker fixing to pack a mass grave.”

“Believe it or not, those’re the good guys,” Rip said.

I snorted, edging toward the nearest table “This more Tex-Mex bullshit?”

“No, a far bigger game,” he said. “Why are you here? There’s no bounties in La Puerta.”

“She was asking about the priest.” Johann’s sneer was back. Guess I should’ve roughed him up more. It was good to know Simon fancied himself a man of the cloth, although what church would have him was beyond me.

“You’re in over your head,” Rip said.

“Seems like that’s for me to decide.” I leaned on the table, disguising the move as a swagger.

“Give me the necklace and get the hell out of here.” Rip’s smile never wavered, but there was a coldness in his eyes–the same sort I’d seen when he had the boys ride down on that village, when I’d left him bloody in the dust for ordering me to do the same. I may be a killer, but I ain’t no murderer.

“I’ll leave when my business is done.”

“If you stay, you’re liable to end up dead, or worse. What’s the priest to you?” He took a step toward me, one hand up, the other in the folds of his duster, as if he hoped I’d forget he had a pistol drawn.

“He’s my goddamn brother.”

The revelation startled Rip enough for me to fling the table at him without getting a bullet between my eyes. There was a crack like a shot from a howitzer and the smell of scorched wood. I was right about the walls; the planks buckled quick as a gutshot cowboy. The clatter of hooves and Rip’s furious curses chased me from the saloon.

The hitching post was empty. I wouldn’t make it far if I couldn’t find Thirsty. There was a moment of panic when I felt a wash of heat on my back, then I saw her. The damn fool had pulled loose from her tethers and gone to the rain barrel around back of the saloon. She splashed in the muddy water, snorting and carrying on like a pig mid-wallow. I sprinted over, snatched up the reins, and tugged her head up. That earned me my glare, until she caught sight of what was behind me. I barely had time to swing a leg over before she was up and running like Old Nick himself was on our tail.

Probably because he was.

![]()

My plan to grab Simon and ride off went out the window soon as I saw the mission. Nestled in the curve of a fast-flowing river, it was built in the Spanish style, with low walls, heavy wooden gates, and about a score of rifle-toting guards patrolling the grounds. They were dressed in robes that looked black in the torchlight, but were probably the same shade of bruised purple as the robes of the man who murdered my Fussy.

I’d holed up in a dry wash close enough to tell none of the guards were my brother. It wasn’t surprising–Simon never had been much for real work. Normally, I would’ve hitched my horse a ways back, but I wanted to keep an eye on Thirsty. Her coat was all black now, and damp to the touch.

“When this is all over, you and I are going to have a long talk.”

Thirsty flicked an ear, staring at the mission like she had half a mind to kick it down. I couldn’t blame her–the place just looked wrong. Something about the way the walls came together at sharp angles but somehow still made a square.

The guards weren’t professionals. It wouldn’t be hard to slip up and over the walls; I only needed to wait for my chance. The thought of just leaving crossed my mind, as it had a dozen times since La Puerta. I couldn’t abandon Simon to Rip’s tender mercies, not like I’d left him to Ma’s all those years ago.

He’d won free eventually, leaving Ma broken and powerless–something of an irony given all them who’d failed to do just that. Her mind was gone when I found her, but she’d died with a curse on her lips, bitter as old rotgut to the last. It didn’t much matter to me; I hadn’t gone to make amends. If it wasn’t for Simon’s telegram, I wouldn’t have gone at all.

They say you can’t go home again, but sometimes you got no other choice.

I carried Ma up to Slaughter Ridge–Simon had named it that on account of how the soil was so full of iron it looked like the hill was bleeding every time it rained. Her body was like to poison most anything, so I burned it. When that was done, I burned the cabin as well. I knew it wouldn’t do a lick of good–Simon had run off with all Ma’s books and tools–but it was still a fine thing to see everything twist away in a column of greasy smoke.

I’d ridden out through a dry ravine that used to be the stream where Simon and I caught toads and beetles for Ma’s night work. I could still see our tiny footprints baked into the hard clay, remnants of a childhood that seemed as foreign as one of those tropical islands sailors are always getting stranded on in the penny novels.

I’d spent my life trying to put some distance between then and now. My only regret was I hadn’t taken Simon with me.

The mission doors creaked open, breaking me from my memories. A half-dozen wagons snaked up the river road, loaded to bear with branches and kindling. Like the rubes they were, the guards clustered around the convoy. I still didn’t see Simon, but it was as good a chance as any to make a run for the walls.

I didn’t bother tying Thirsty up; if she wanted to follow there wasn’t much a halter would do to stop her. When I glanced back, though, she was just watching me, still as a boulder.

I sprinted to the mission quietly as I could, vaulting up to catch the lip of the wall. The stone was warm and slimy beneath my fingers, but my grip held. I hauled myself over the wall and into the skeleton of a garden. What plants remained were strange, bulbous things, their leaves bent and fluted like corrugated tin roofs.

A few low buildings crowded around an old church, its bell tower somber as a gallows tree. I had a good hunch that was where Simon was. The guards were busy piling the wood in the center of the courtyard, and didn’t raise a cry as I stalked along the wall and into the open doors.

Moonlight slanted through the dusty windows, picking out stone columns and an altar at the far side of the room. The sight of sigils etched into the stone was strange, but the mingled scents of old books, oiled steel, and blood were familiar as an old glove.

It smelled like home.

“I was worried you wouldn’t make it.” Simon’s voice seemed to come from all around.

“I came for you.” The darkness swallowed my declaration. “It’s not too late to get clear of whatever this is. I can help you.”

“You’re right.” My brother stepped from behind a nearby pillar, his smile bright in the glow of the full moon. “You can help me.”

Shapes moved in the hungry gloom, shadows with no maker. I drew my Colt, but before I could so much as thumb back the hammer, the corners of the room swallowed me whole.

![]()

It wasn’t the pain that woke me–Ma’s Athame was sharp as fresh grief–but the metallic tang of hot blood. When I tried to bring a hand to my face I found my wrists and ankles bound. They’d dragged me out into the courtyard, the mountain of kindling looming like a judge on his high bench. Men and women in purple robes stood in a loose semicircle around the pile, their expressions watchful, but excited.

“Dru, nice to have you back.” Simon drew another line of fire along my arm, catching the blood in a golden bowl. “Just like old times, isn’t it?”

I grimaced. It wasn’t exactly like old times–we’d never done the cutting.

“Sorry about this, but I need your blood to consecrate the relics. I have them all, you know…well, except the one.” He glanced at the gold choker on my neck. “No opener has ever managed a whole set, you know.”

Simon looked about to continue when a furious whinny echoed through the courtyard, followed by curses and gunshots.

I strained against the ropes. My fingertips brushed the snub handle of my derringer–damn fools hadn’t thought to search my boots. There were more shouts from out front, a heavy splash, then silence.

“If you hurt her, I’ll–”

“Another pet, Dru? I had hoped you’d grown out of that. What are you calling her…Missy, Prissy, Fishy?”

“Thirsty,” I snapped back.

“Predictable.” Simon chuckled.

A woman in purple robes dashed into the courtyard, clutching her arm like it was broken. “The kelpie made it to the river, dragged Zeke and Ephraim down with it.”

Simon twirled a lazy hand. “Let the beast go. After all, we’ve got the collar.” He fingered my necklace. “Your pet is a spirit of the deeps, ancient and terrible. You don’t want to be bound to something like that. Give me the collar.”

“Take it yourself.”

“I can’t, not while you live.”

“Then you’ve got a problem, because I ain’t giving it up.”

My brother’s lips writhed like a dying snake, his knuckles whitening on the bone handle of the Athame. I could see him struggling to tamp down his anger, but I didn’t care. I was sick of being shuffled around like a piece in some damn game. I hadn’t let Ma use me like that, and I wasn’t going to let Simon, either.

“Dru, please, I don’t want to kill you.”

“Then why’d you send your man to bushwhack me?”

“Zachariah wasn’t my man. We were on the same side, yes, but he thought to claim the power for himself. To use your blood to supplant me.”

“Why do you need my blood?”

He knelt next to me, a sorrowful twist to his mouth. “I would have used my own, but I need it for what is to come. We are not wholly of this world, you see. Our father–”

“Our father was a tinsmith out of Amarillo.”

“That’s what mother wanted us to believe. She was going to steal our birthright, but not now. Zachariah was a fool. I knew you could take care of yourself, Dru. You always have.”

There it was, my shame. Simon was my brother, and I’d abandoned him. “I’m sorry for leaving you with her.”

“Sorry? I’m grateful. Oh, it was hard at first, but I watched and learned. Mother was so wrapped up in preparations, she hardly noticed. I’m twice the witch she ever was. I proved it to her. Did you see?”

“I saw.”

“All of it was for this.” He gestured at the woodpile. “And I took it from her. I’ll be the one to witness the Old Ones set free, I’ll be the one they lift up, and I’ll be the one who sits at the right hand of our father.”

I would’ve called him crazy, but something more than the glint in his eyes gave me pause. There was an electricity–no, a heaviness in the air. The darkness felt tight as a drumhead, as if something was pressed up against it.

“Not much time, now.” Simon regarded his blade thoughtfully, his gaze sliding to my throat. The regret in his eyes was replaced by something cold and hard. “I wanted you to see the opening, but–”

A call from outside brought him up short.

Rip, Johann, and the rest of the La Puerta irregulars came marching into the courtyard. Any hope I had of rescue died when I saw their faces. They looked like men fixing to charge uphill into a hail of grapeshot. Even Johann’s devil wore a hangdog expression.

Simon stood, dusted off his knees, then drew a wand from his robes. “This is the best you could do? Two washed-up immortals, a charlatan, and a gaggle of drunken brujas?”

Rip said nothing, only pulled a wand from his vest–a twin to Simon’s own.

“A moment, gentlemen.” Simon dipped the wand in my blood, chanting under his breath. Others stepped from the crowd bearing cups, icons, and assorted relics, which Simon gleefully anointed. With each, my brother’s smile grew wider, and Rip’s more somber.

“Cut me free, Captain.” I struggled to a sitting position, then fell back as the world seemed to upend itself. I guess I’d lost more blood than I thought. Still, the move let me palm the derringer.

“Sorry, Fran, there ain’t nothing for it.” Rip glared at Simon. “Light the damn thing.”

“If you insist.” Simon lit a torch and held it high.

A feeling of mounting dread crawled up my spine, slick and leggy as a millipede. The atmosphere in the courtyard felt stifling as an Austin summer and thin as the air in a mountain pass.

Things shifted behind the darkness. I knew they saw me. Worse, I knew they recognized me. Everything around us seemed flat as paint on canvas–depth, light, shadow; time no more than an artist’s tricks.

“Do you see, Dru?” Simon looked down at me, face shining with mad joy. “Do you see?”

I saw well enough. My brother wasn’t fixing to light just any fire, he meant to burn everything away. I couldn’t stop him as I was–bloody and trussed like a Sunday roast–so I did the only thing I could think of.

I whistled for my horse.

For a moment, nothing happened apart from everyone staring at me like I’d started singing campfire songs. Then it came–the rattle of hooves, the pounding of surf building like a storm. A wave crashed through the wall, the water dark as a broken promise. It slammed into me with enough force to drive the air from my lungs. Somehow I managed to keep hold of the derringer. Just as I was about to fill my lungs with ice water, something took hold of my collar and dragged me into the air.

Thirsty had come, and she’d brought the river with her.

“Good girl,” I sputtered between great gulps of air. The courtyard was knee-deep in water, bodies and bits of wood floating on the choppy surface. Simon struggled up, hair slicked flat, robes plastered to his bony chest.

“Try and start your goddamn fire, now,” I said.

“You think this will stop me?” He sloshed toward me, knife in one hand, wand in the other. “I didn’t want to do this, but you’ve left me no choice. Why couldn’t you just leave well enough alone, Dru? It’s what you do best.”

Thirsty flowed toward him, terrible as a riptide.

Simon pointed the wand at her, and she gave a shriek like a kettle on the boil. Great billowing clouds of steam rose from her flesh as she sank back into the water. My brother advanced, not even the barest flicker of emotion on his face. It was a look I remembered well, although one I’d never seen him wear. I knew then there was no pulling him out. He’d become what Ma made him, what I’d been too afraid to save him from. Even so, he was my brother, my responsibility.

Simon knelt beside me. “I’ll give Father your regards.”

Hot tears stung my eyes as I twisted to press the derringer to his chest. “I’m sorry.”

There was a pop like that of a champagne cork. Simon looked down, blood almost invisible against the crushed violet of his robes. He sat down in the water, anger melting to surprise. The Athame slipped from his hands. I squirmed to grab it, then wedged the handle between my boots so I could saw through my bonds.

“That’s against the rules.” His accusation was almost a whisper as he slumped against the wall.

“I ain’t playing your damn game.”

The look he gave me was equal parts pain and reproach, but I’d done what I had to. Only cowards don’t take care of their own.

Simon gave a single painful swallow, and fell still.

There were shouts, then a flurry of splashes as those of Simon’s flock who’d survived the flood fled into the night. I held my brother’s body for a spell, wondering if there’d been a single moment when the boy I knew died, or if slow starvation of the spirit had made him like this.

A shadow fell over me. Rip looked like a drowned cat, but the smile on his face was warm as a Mexican sunrise.

“You really saved us back there, Fran. Not just us, everything. How’d you know the kelpie would bring the river?”

“My brother said it was a water spirit. Just a hunch.”

“That was some quick thinking. I could use someone like you in the Rangers.”

“They don’t take women.”

“We could change that.”

I looked up at him. “I think I’ve had about enough of other people telling me what to do.”

I stood to shouts and back slaps from those of the La Puerta crew who were still alive.

The Mandarin joined Rip, sketching a deep bow. “Madame, you have my undying gratitude. I am Han Wu–”

“I don’t much care who you are, who any of you are.” I was getting damn sick of fellas who thought everything was about them. I pushed through the stunned crowd, looking for the only thing that still mattered to me.

To my relief, Thirsty rose from a ripple of water, her coat oil-slick black, her mane like fronds of pond grass. Strangely, she came saddled, my carbine in its holster and my gunbelt hanging from the saddle horn. She whickered appreciatively as I ran my fingers through her mane before pulling myself onto her back.

“Where you headed, Fran?” Rip called after me.

“Don’t know, and if I did, I sure as hell wouldn’t tell you.”

I could’ve stayed, I suppose, could’ve been all they wanted me to be, but soon enough everything would start to chafe, and like a fly battering itself against a windowpane, I’d either have to get out or kill myself trying. It had always been like that for me, but at least now I knew why. Wherever I went people said it was because I wasn’t from around here–wherever here happened to be. If Simon was right about Pa, I might not be from around anywhere.

I reckon that suited me just fine.

The moon looked down on us, bright and round as a silver dollar. There was a chill in the October air, but a change of clothes and a few hours on the trail would take the edge off. It felt good to be in the saddle again, and even better to feel, for the first time, like I wasn’t running from something.

I patted Thirsty’s neck. “You know, girl? After all that, we’ll have to give you a new name.”

The night was silent but for our breathing, and the steady thud of her hooves. Sweeter music I’d never heard.

I blinked back tears. “Hell, I might even need one, too.”

By day, Evan Dicken fights economic entropy for the US Department of Commerce, and researches Edo period cartography at the Ohio State University. By night, he does neither of these things. His work has most recently appeared in: Daily Science Fiction, Innsmouth Magazine, and Toasted Cake Podcast, and he has stories forthcoming from publishers such as: Chaosium, Andromeda Spaceways, and Woodland Press. Feel free to drop by and visit him at: www.evandicken.com.

By day, Evan Dicken fights economic entropy for the US Department of Commerce, and researches Edo period cartography at the Ohio State University. By night, he does neither of these things. His work has most recently appeared in: Daily Science Fiction, Innsmouth Magazine, and Toasted Cake Podcast, and he has stories forthcoming from publishers such as: Chaosium, Andromeda Spaceways, and Woodland Press. Feel free to drop by and visit him at: www.evandicken.com.

If you enjoyed this story, let Evan know know by commenting — and please use the Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus buttons below to spread the word.

Story illustration by Christoph Schulz and Anthony Pearce.

I’d never thought to find a Kelpie in a western themed tale, but you did honors to this one nicely, great story.

LikeLike

Beautiful work, Mr. Dicken. Gotta love the Kelpie. I’ve been reading both Zelazny and Lovecraft lately, so this was a bizarre and welcome coincidence.

LikeLike

Thank you all so much. I’m glad you enjoyed the story, and honored by the opportunity to pay tribute to the author and novel who shaped my reading (and writing) habits.

LikeLike

It’s been a long time since I met a Kelpie in a story. Thank you very much. Well done.

LikeLike

Great story!

LikeLike

Nice story, reminds me of RE Howards western tales . Well done

LikeLike