Do you recall a simpler time, when the fires of patriotism stirred you? What was it like?

Do you recall a simpler time, when the fires of patriotism stirred you? What was it like?

When I was in grade school, a music teacher came around to each class. A phonograph rode her music cart. One day, she played the Stars and Stripes Forever by John Philip Souza. Above the crash of drums, the clash of cymbals, and the thunder of brass soared a shrill piccolo that danced like a wraith among the stars on the field of blue on the U.S. flag.

As I grew older, I learned the dark side of U.S. history. Such revelations shook my faith.

Despite America’s failures, I believe the United States remains a noble experiment.

The Declaration of Independence of 1776 inspired the Founding Fathers to defy England, once the most powerful Nation on earth. Later, America struggled against the forces of the Hun in World War I, the fanatics of the Axis in WW II, and the fires of Communism during the Cold War.

Repeatedly, the United States stopped despots from dominating the World.

Out of the same National test-tube arose the furnace of free-opportunity. And from that crucible appeared self-made men, the titans of industry, the Andrew Carnegies of yesterday, and the Bill Gates of today. Each embodied a rags-to-riches fantasy, the idea that someone of low birth, can break out of his or her inherited station in life, climb the social ladder and become a success.

Tanked-up patriotism and trickle-down economics also spawned literary heroes. Out of the imagination of “Two-Guns Bob” Howard stamped mighty Conan, moody Solomon Kane, and mystic King Kull. Their brains, brawn, and slicing blades triumphed over dark wizards, dynastic lords, and dim gods.

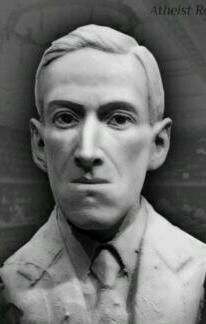

Remarkably, from the same patriotic primeval soup emerged H.P. Lovecraft and his Cosmicism.

In this article, I would like to first explore a few reasons why H.P. Lovecraft’s writings have remained relevant. Next, I want to explore two areas where Cosmicism confronts American Idealism. One is American Economics. Two is the United States’ version of Technological Optimism.

H.P. Lovecraft Followed His Inner Artistic Vision:

H.P. Lovecraft wrote outside the American mainstream of his time. HPL did not write like Dale Carnegie, To Win Friends and Influence People. Nor did He write like Napoleon Hill, To Think and Grow Rich.

Yet, as Howard Philips stayed true to his inner artistic vision, his words inspired many. Like Painter Vincent van Gogh and Poet Dylan Thomas, Lovecraft epitomized the starving artist, One who did not compromise his creativity for commercialism.

The Philosophical Wastelands of Rank-and-File Pulp Fantasy:

Why do Lovecraft’s words still carry weight, while other pulp writers are wholly out-of-print?

In the heyday of Pulp, many stories shared three features.

One, some writers sidestepped thought-provoking plots. Storylines involved finding the simplest formula to sell a story. Often, that meant fulfilling a nostalgic longing for past glories. A cowboy’s struggle to survive on Mars rehashed the two-fisted exploits of Wyatt Earp in Tombstone, Arizona.

Two, many authors steered clear of philosophical binds. The black and white values of the American Frontier – of good and evil, right and wrong, the innocent and the guilty – did not upset a reader’s worldview. No one questioned who the Good Guy and Bad Guys were.

Three, other writers ignored scientific facts. Myriad incarnations of Flash Gordon and Buck Rodgers broke the speed of light, as they tracked down the countless avatars of Ming the Merciless, the notorious Fu Manchu or the ruthless Genghis Khan. And the ray gun of tomorrow, like the six-gun of yesterday, made a human being the equal of any alien.

The result: people forgot those tales, like the serial westerns of Saturday morning cinemas.

Lovecraft had an opinion about tales like Outer Space Westerns:

“…To me there is nothing but puerility in a tale in which the human form—and the local human passions and conditions and standards—are depicted as native to other worlds or other universes…” (1)

I am not painting Robert E. Howard’s fiction with this same broad brushstroke. REH’s works throb with life and on his words hung blood, flesh and bones. And his wide-reading of myths and histories, added realism to the fictional lands and epochs that his heroes galloped through.

Where HPL was cerebral, REH was corporeal. For Lovecraft: “…atmosphere, not action, is the great desideratum of weird fiction” (2).

One Key to Lovecraft’s Enduring Popularity:

One means HPL used to enhance the atmosphere of a piece was; he framed his fiction in fact. People often mistake a cubic zirconia for a diamond, if it is set in a solid gold setting.

And that’s one of the things HPL did well.

The Scientific American reflected on Lovecraft’s pioneering use of science in his tales:

“Lovecraft is today considered one of the first authors to mix elements of the classic gothic horror stories, mostly characterized by supernatural beings, with elements of modern science-fiction, were the threat to the protagonists results from natural enemies, even if these are creatures evolved under completely different conditions than we know. He was an enthusiastic autodidact in science and incorporates in his story many geologic observations made at the time, he even cites repeatedly the geological results of the 1928-30 expedition led by Richard Evelyn Byrd” (3).

Several tributaries of human knowledge – the Origins of Darwinism, the Cosmos of Galileo, the Collectivism of Karl Marx, the History of Oswald Spengler, the Philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, as well as other forces of the enlightenment – flowed together like a river in Lovecraft’s Cosmicism.

In his writings, Lovecraft brooded over the proper attitude of the thinking man towards an indifferent Universe. And out of that birthing process, arose Azathoth, Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep, Yog-Sothoth and other alien/deities in Lovecraft Pantheon.

Some Tenants of Cosmicism:

Like a beam of light shot through a prism, there are many facets to Cosmicism.

Cosmicism sees the human race and all its “civilization” as senseless against the backdrop of Deep Time:

“The Universe is only a furtive arrangement of elementary particles…The human race will disappear. Other races will appear and disappear in turn. The sky will become icy and void, pierced by the feeble light of half-dead stars. Which will also disappear. Everything will disappear. And what human beings do is just as free of sense as the free motion of elementary particles. Good, evil, morality, feelings? Pure ‘Victorian fictions’. Only egotism exists” (4).

Moreover, Cosmicism says that beyond the “reality” defined by our five-senses, human norms are not normal:

“Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large…To achieve the essence of real externality, whether of time or space or dimension, one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all. Only the human scenes and characters must have human qualities. These must be handled with unsparing realism, (not catch-penny romanticism) but when we cross the line to the boundless and hideous unknown—the shadow-haunted Outside—we must remember to leave our humanity—and terrestrialism at the threshold” (5).

What we think is important is irrelevant to everyone else, everywhere else. The Universe is a cold, uncaring place.

Elements of the American Dream Expressed in Economic Order

There are three parts of the American Dream I would like to discuss:

- Rugged Individualism.

- The Protestant (or Puritan) Work Ethic.

- America’s Version of Technological Optimism.

After we define each element, I will assess each ideal against a related ingredient of Cosmicism and HPL’s opinions.

Rugged Individualism:

First, let us review Rugged Individualism.

Rugged individualism believes that nearly everyone possess the ability to succeed, despite the obstacles.

According to the American Dream, the United States is a land of limitless opportunity. Individuals can rise as far as their merit and drive takes them. A person’s worth consists of their abilities, education, hard work, positive attitude, and integrity. Self-reliance equals independence. A person gets out of the system what they invest in it. You get as much skin out of the game, as you put skin in the game.

Americans, largely, still believe that is how to get ahead.

Rugged Individualism inspired William Ernest Henley to write the familiar words of the poem:

Invictus

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tear

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

Early Lovecraft and “Americanism”:

Early Lovecraft and “Americanism”:

In 1919, at the age of twenty-nine, Lovecraft penned an essay entitled “Americanism”. In it, HPL expressed an attraction for elements the American Dream:

“Americanism is…the spirit of truth, honour, justice, morality, moderation, individualism, conservative liberty, magnanimity, toleration, enterprise, industriousness, and progress—which is England—plus the element of equality and opportunity caused by pioneer settlement” (6).

And HPL believed in some upward mobility that was unique to Americanism:

“But the features of Americanism peculiar to this continent must not be belittled. In the abolition of fixed and rigid class lines…[permits] a steady and progressive recruiting of the upper levels from the fresh and vigorous body of the people beneath. Thus opportunities of the choicest sort await every citizen alike, whilst the biological quality of the cultivated classes is improved by the cessation of that narrow inbreeding which characterises European aristocracy” (7).

Yet, in the same discourse, HPL felt the benefits of Americanism were only available to certain races:

“Most dangerous…of the several misconceptions of Americanism is that of the so-called ‘melting-pot’ of races and traditions. It is true that this country has received a vast influx of non-English immigrants who…enjoy without hardship the liberties…our British ancestors carved out in toil and bloodshed. It is also true that…[Those who] belong to the Teutonic and Celtic races are capable of assimilation to our English type and of becoming valuable acquisitions…It does not follow that a mixture of…alien blood or ideas…can accomplish anything but harm” (8).

Lovecraft’s racism is well documented. A discussion of that trait is beyond the scope of this work. I would like to point out that HPL suffered from a phenomenon that afflicts many learned people.

Just because a person is correct in one area, does not mean their opinion is the gospel truth in another. And often, the person speaks from a theoretical viewpoint, not the hard-earned truths won in crucible of experience. At this juncture in his life, I believe HPL drew the conclusions in “Americanism” from theory, opinion, and obvious prejudice.

Later Lovecraft, Cosmicism and “Rugged Individualism”:

Cosmicism sees “Rugged Individualism” as an outgrowth of Egotism, an expression of man’s ignorance.

First, the skills that allow an individual to dominate a limited economic Universe may prove useless in the unlimited Universe.

In 1936, some seventeen years since Lovecraft penned his article, “Americanism”, his opinion about the free enterprise and upward mobility changed. Here, Lovecraft related how Laissez-faire capitalism was inadequate, even in the face of the cosmos defined by history and science in his day:

“As for the Republicans—how can one regard seriously a frightened, greedy, nostalgic huddle of tradesmen and lucky idlers who shut their eyes to history and science, steel their emotions against decent human sympathy, cling to sordid and provincial ideals exalting sheer acquisitiveness and condoning artificial hardship for the non-materially-shrewd, dwell smugly and sentimentally in a distorted dream-cosmos of outmoded phrases and principles and attitudes based on the bygone agricultural-handicraft world, and revel in (consciously or unconsciously) mendacious assumptions (such as the notion that real liberty is synonymous with the single detail of unrestricted economic license or that a rational planning of resource-distribution would contravene some vague and mystical ‘American heritage’…) utterly contrary to fact and without the slightest foundation in human experience? Intellectually, the Republican idea deserves the tolerance and respect one gives to the dead” (9).

If rugged individualism and Laissez-faire capitalism were “…utterly contrary to fact…” – and both contributed to the Great Depression – then what value do they have beyond the threshold of terrestrialism?

Could Donald Trump wheel a deal with Great Cthulhu? Would “The Donald”, that arch “rugged individualist/industrialist” of today, fare any better than “food” for the Big “C”, or “fodder” squashed under its shambling immensity?

Would “The Donald” make a good incubator? If an Old One’s took ten thousand years, before it ripen and emerged from its shell – what a way to spend eternity.

Second, what human beings value commercially may have little trade value to other civilizations. An episode of the original Twilight Zone, entitled The Rip Van Winkle Caper, illustrates how the value of valuables can change.

After a gang steals a million dollars in gold, they secret away the loot and themselves to a hidden desert cave. There the leader has prepared suspended animation chambers, where they hope to lay low – say for a hundred years – until the heat dies down, and the robbery is long forgotten. When they awake a century later, so does their greed. One by one, the gang kills each other off, until only the leader remains. When he emerges with his horde, he finds that Gold is worthless. Humanity learned how to cheaply manufacture the element decades earlier.

The moral of the story: if humanity thinks we could barter our way to a better bargaining position with our trinkets or treasures before a Great Old One, we are sadly mistaken.

The Protestant or Puritan Work Ethic:

Next, I will sketch out a classic understanding of the Protestant (or Puritan) work.

The primary aim of life, the purpose of a human being’s “creation” is work. The three keys to work that please “God” are industry, hard work and thriftiness. As people excel in those “ascetic” disciplines, the resulting increase of goods is an earthly “sign” of their eternal salvation. When a person engages in those self-restraints, he or she pursues a “holy” life.

When a person rests in their possessions and enjoys their wealth, Idle-hands and minds become the devil’s playground. One’s “salvation” comes into question.

God allegedly builds “rewards” in the fabric of the universe. As a person pursues the triad of “holiness”, preordained circumstances and opportunities flow in the engaged person’s direction.

You do not have to be “religious” to be influenced by the Protestant Work Ethic. As one article put it:

“…Residents of…other countries are…baffled by the frantic ‘workaholism’ typical of the U.S… if they work…hard, it’s because they…make a conscious decision in favor of it. Most U.S. people, on the other hand, seem psychologically impelled to work much too hard for no obvious reason. Many of us…feel guilty if we aren’t working much too hard. And we tend to think very highly of people who hate what they do; that is irrationally seen as somehow more virtuous than having a job one loves! This workaholic attitude is often treated (by people in the U.S.) as just common sense, just part of human nature. It’s not. It’s a distinct phenomenon, only a few centuries old [and], localized to a few areas of the globe…” (10).

Lovecraft rejected the Puritan Work Ethic for both principled and personal reasons.

One, Lovecraft believed the separation of civil and religious institutions shielded Americans from ecclesiastical oppression:

“Total separation of civil and religious affairs, the greatest political and intellectual advance since the Renaissance, is also a local American…particularly a Rhode Island…triumph. Agencies are today subtly at work…to impose upon us through…political influences the Papal chains which Henry VIII first struck from our limbs; chains unfelt since the bloody reign of Mary, and infinitely worse than the ecclesiastical machinery which Roger Williams rejected. But when the…relation of intellectual freedom to…Americanism shall be…impressed upon the people, it is likely that such…undercurrents will subside” (11).

Lovecraft, uncomplicated in his atheism, would reject any religious influence that affected people. Especially, if such a religious idea was as pervasive throughout society as the Protestant Work Ethic.

Two, Lovecraft devised a scene that satirizes the illogic of the Puritan Work Ethic in The Quest of Iranon (1921).

HPL typed Iranon as a musician, who follows whatever lyric he fancies. During his journey, Iranon enters the City of Teloth at night, and lodges there. In the morning, a leading citizen of the town leads Iranon to a cobbler’s shop. Iranon is informed, he must abandon his music, and take up the trade of cobbling.

“’But I am Iranon, a singer of songs,’ he said, ‘and have no heart for the cobbler’s trade.’

‘All in Teloth must toil,’ replied the archon, ‘for that is the law.’

Then said Iranon: ‘Wherefore do ye toil; is it not that ye may live and be happy? And if ye toil only that

ye may toil more, when shall happiness find you?’…

But the archon…did not understand, and rebuked the stranger.

‘Thou art a strange youth, and I like not thy face or thy voice. The words thou speakest are blasphemy, for the gods of Teloth have said that toil is good. Our gods have promised us a haven of light beyond death, where shall be rest without end, and crystal coldness amidst which none shall vex his mind with thought or his eyes with beauty…All here must serve, and song is folly”.

Plainly, Lovecraft fleshed out his disdain for the Puritan Work Notion in the guise of the hard-working but unhappy citizens of Teloth.

Three, some aspects of Cosmicism stand in stark contrast to this tenant of the American Dream:

- There is no God, who keeps track of good deeds, and rewards each person for those good acts.

- There is no afterlife; only the here-and-now exists.

Why should Americans work themselves to death in some cases, in jobs they do not like, for some eternal reason, when none exists? Why should American feel guilty about enjoying the fruits of their labors, simply because the time spent on leisure is time spent away from working and making money?

And why should a person live his or her here and now in a self-impoverished way – working too many hours at something that robs meaning from their life – for a better afterlife that doesn’t exist?

I know these are rhetorical questions, but I believe they convey the points I want to make. And even if you do not buy into a religious reality, the American cultural expectations that grew up around the Puritan Work Ethic can affect how your approach work, see wealth, and view leisure time.

Four, Lovecraft’s personal values conflicted with the Protestant Work Ethic.

HPL stylized himself an eighteenth-century amateur gentleman. Throughout his life, Lovecraft was torn between the professional writer’s desire for success and money and the detached, amateur gentleman’s desire to reach for aesthetic goals unconstrained by commercial requirements (12). Beyond those dynamics, the pressures of poverty constantly distracted him.

Had Lovecraft bowed to commercialism, he might have lived better. If he internalized the Puritan Work Ethic, his lot in life might have improved. But such idolatry betrayed HPL’s inner convictions. And work for work’s sake, felt beneath his dignity.

Technological Optimism as a Blend of Science and American Idealism:

Now, let us examine Technological or Scientific Optimism that flowers in America.

The Enlightenment taught there is order to the Universe. Laws govern the Universe and regulate how it acts. Since there is a structure to the cosmos, it is possible to discover those laws through science.

Pragmatism is a second element. What works is right. What functions is true. Ideas are instruments or tools for prediction, action, and solving problems.

American exceptionalism is a third element. Americans bring the right blend of personal freedom, creativity, taking responsibilities for a desired outcome, and economic incentives to solve any problem. Americans possess a Can-Do attitude. Where there is a will – an attitude that explores all options – there is a way.

What do you get when you combine science, pragmatism and American Exceptionalism? You get the Technological Optimism.

Aspects of Technological Optimism:

Technological optimism believes that there will be a continual stream of scientific and technological advances.

For example, as scientists create new hybrid crops, one farmer can raise more bushels per acre. Such breakthroughs free people from the labor-intensive farming needed to support past civilizations. Fewer citizens spend their days tilling the soil, to feed their families.

While the philosophy can be found elsewhere, I believe the Credo of Scientific Advancement finds fertile ground in America. Think about President Kennedy’s challenge to America: land a man on the Moon within a decade. Institutions like NASA responded, and Neil Armstrong uttered the famous: “…That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind…”

Americans also love new gadgets. People stand in long lines, at times overnight, every time a new Apple IPhone is introduced.

Champions of scientific advancement also see a brighter tomorrow, as new technologies impact people.

Facebook and Twitter reshape how people relate to one another. For instance, of the fifty-four million singles in the United States, a full forty million have tried online dating (13).

The internet restructures human institutions. When news is instantaneous, available from several sources, and from different political views, citizens can hold their government responsible for its actions.

To understand the impact of internet, consider the fact that 12 countries, not only censor news and information online but also systematically repress Internet users:

“Bahrain North Korea

Belarus Saudi Arabia

Burma Syria

China Turkmenistan

Cuba Uzbekistan

Iran Vietnam” (14).

Technology reforms how people spend their workdays. Once, keyboards were attached to typewriters. And typewriters were largely found on reporters, secretaries and students’ desks.

Now everyone has a keyboard connected to a computer. And while computers have increased the average worker’s productivity, keyboard-related illnesses such as carpal-tunnel syndrome have arisen (15).

Technology restyles how people relate to nature. Safety Nazis teach children to fear the outdoors. Grade schools everywhere ban outside activities, once thought innocuous by past generations. And children, attached to IPhones and hand-held Nintendo games like fledgling Borgs, have forgotten how to play.

Science may recast human’s evolution. Humans have not changed much genetically in the past 100,000 years. The future holds miniature nanobots coursing through our veins. That technology and advanced gene therapy, can lead to advances in healing (16). Aging might be reversed by nanotechnology; such reconstructions might lead to improving on basic human beings. Designer choice, not Darwinian chance, could guide (or misguide as the case may be) the next steps of human evolution.

Technological optimism also believes scientific advances will overcome any future problem humanity faces. Star Trek represents one technological optimist’s view of humanity’s tomorrows.

Man’s Inept Senses:

One, Lovecraft went beyond Kant, in defining what could be known. To Kant, humanity’s senses created a dualism. There was the Noumena, the true essence of an object and the Phenomena, how our senses rightly or wrongly interpreted the object.

Plato’s allegory of “The Cave” has a similar meaning. In that analogy, people live out their lives, chained to the wall of a cave. In turn, they face a blank wall. The people watch shadows projected on the wall by things passing in front of a fire behind them. They spend their lives, ascribing names and content to these shadows. The shadows are as close as the prisoners get to viewing reality. However, the shadows on the wall do not make up reality at all. They are shadows of reality.

Unlike Plato, Kant saw no escape from the cave.

Lovecraft’s Cosmicism says, even if man’s senses were accurate and able to see an object as it truly is, man is still deficient.

“What do we know … of the world and the Universe about us? Our means of receiving impressions are absurdly few, and our notions of surrounding objects infinitely narrow. We see things only as we are constructed to see them, and can gain no idea of their absolute nature. With five feeble senses we pretend to comprehend the boundlessly complex cosmos, yet other beings with wider, stronger, or different range of senses might not only see very differently the things we see, but might see and study whole worlds of matter, energy, and life which lie close at hand yet can never be detected with the senses we have” (17).

Since our senses evolved to gauge three dimensions, our senses lead us to believe in illusions. Our limited senses blind us to the reality of other dimensions. We are limited by a three-dimensional brain, and the inability to “see” the fourth dimension is like that of a blind man attempting to conceive the concept of color.

Those who make confident assertions about the contents of other dimensions are sadly mistaken:

“…we are like carps swimming contentedly in the pond, confident that our Universe consists of only those things we can see or touch, of the familiar and the visible, refusing to admit that parallel universes or dimensions can exist next to ours, just beyond our grasp…” (18).

Outer space, as we perceive it, exists “out there”; and inter-dimensional space exists here, all around us. Behind the tedium of our ordinary world, the perils enumerated in Cosmicism lurk. They poke through our ignorance.

Brown Jenkins and the homicidal Witch Keziah Mason dealt death through the dreams of Walter Gilman. The Necromancer Joseph Curwen reached out of the past and out of the dust to extinguish the life of his benefactor, Charles Dexter Ward. Innocent sailors die, after they release the imprisoned demigod Cthulhu, hidden for an eternity beneath the placid Pacific. And the Father of chimeras like Wilbur Whateley dwell somewhere in the outer spheres, over the rainbow, waiting for release and revenge.

All the dangers of Cosmicism lurk closer than most of us dare think:

“‘You see them? You see them? You see the things that float and flop about you and through you every moment of your life? You see the creatures that form what men call the pure air and the blue sky? Have I not succeeded in breaking down the barrier; have I not shewn you worlds that no other living men have seen?’ I heard him scream through the horrible chaos, and looked at the wild face thrust so offensively close to mine. His eyes were pits of flame, and they glared at me with what I now saw was overwhelming hatred. The machine droned detestably” (19).

Will American Plant the Stars and Stripes in the Dunwichian Outer Spheres?

Typically, Americans want to plant the Stars and Stripes on any new territories they reach, especially if the venture is the crowning achievement of a series of technological breakthroughs. Often, the urge to explore centers around the same compulsions that drove Columbus to the Western Hemisphere:

- The first motive was curiosity. The desire to learn and understand the wider world was a fundamental value of the Renaissance.

- A second motive was religious. The age is connected to the idea of the Crusades of the 12th and 13th centuries — a religious desire to save souls.

- A third motive was economic. Islam controlled the routes to riches in the east. If a different route were found – one that avoided the Ottoman Empire – gold, silver, and spices were there for the taking.

- A final motive was imperialistic. As naval technology advanced, Europeans tried to colonize foreign lands, as the ancient Greeks and Romans did.

Scientific zealots and go-for-broke adventurers often do not have the means to fund such schemes. The purse-string holders will not cough up a cent unless they see the potential for profit from such exploration. Or a leader may fund such a scheme, because of the all-consuming desire for an enduring legacy.

How about placing a Mount Rushmore-like monument to your Presidency on Mars?

Even now, the String Theory introduces us to the extra-dimensional spider webs spun all around us. Will explorers and ne’er do wells, using a technological trapezohedron, enter another dimension, hit a tripwire, and draw down an elder terror into our terrestrial realm (20)?

Humanity’s Inadequate Comprehension:

Two, humanity lacks the ability to understand or correlate all the implications inherent in the truth of an object (21). Humanity’s knowledge was once limited enough for a Universalist, like Leonardo Da Vinci or Archimedes, to comprehend all of fields of study as a whole.

Beyond Leonardo, Mozart, Tesla and Einstein were intellectual giants, able to conceptualize vast amounts of information, as experiments worked out inside their heads. But those historical luminaries, while savants in their own fields, were seldom in others.

Man lacks the length of life to understand the Cosmos. When people die, they leave all of their accumulated knowledge behind. The next generation has to start all over again on the learning curve.

As artificial intelligence become sentient, computers will pass their aggregate memes, learning experiences, nuances and vast store of memories from one generation of machines to the next. They will have the ability to pick up right where the last generation left off without any information lost.

At that juncture, such cybernetic beings, unless they have a nostalgic reason for keeping humans around, or someone had the insight to install Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics into the machines:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

or unless there was a Borg-like need for input from a corporeal species, the cyborgs might decide to terminate the lesser genus.

Humanity’s Inaccurate Grasp of Danger:

Three, will Americans researchers inevitably doom our species due to blind technological optimism?

The blinding effect of technological optimism – casting caution to the wind, in the pursuit of scientific research – can be seen in the following quote – bringing alien life to earth:

“Humans will be able to recreate alien life forms and ‘print out’ organisms using the biological equivalent of a 3D printer in the future, a DNA pioneer has predicted… [Dr Craig Venter] wrote: ‘The day is not far off when we will be able to send a robotically controlled genome sequencing unit to other planets to read the DNA sequence of any alien microbe life that may be there. If we can . . . beam them back to Earth we should be able to reconstruct their genomes…The synthetic version of a Martian genome could then be used to recreate Martian life on Earth’” (22).

Blind obsession with science leads to causalities among the expendable populace – the rank-and-file American Citizen. In Alien Resurrection (1997), one nonessential personnel stated to an obsessed scientist, “Doctor, that thing that killed my partner …that’s your pet science project?”

Lovecraft saw science as a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde entity. Dr. Jekyll was moral and decent, a charitable person with a reputation as a courteous, genial man. HPL fell in love with that gentlemanly science as a youth, when Astronomy infatuated him.

HPL also saw the Mr. Hyde, the darker, psychotic side of science. Herbert West was a doctor without intellectual peer. Yet, Dr. West’s zeal for scientific research thought nothing about the carnage his necromantic experiments entailed.

I am not sure what scientific news or discovery soured Lovecraft’s initial passion for science. I think it went beyond his shortcomings in algebra, the intellectual hurdle that stopped him from becoming an Astronomer. Yet, anytime scientific progress appeared in his works, he sees trouble:

“Life is a hideous thing, and from the background behind what we know of it peer daemoniacal hints of truth which make it sometimes a thousandfold more hideous. Science, already oppressive with its shocking revelations, will perhaps be the ultimate exterminator of our human species — if separate species we be — for its reserve of unguessed horrors could never be borne by mortal brains if loosed upon the world.” (23).

The dark side of science plagued “men” of all epochs and all species.

Think of the Elder Things, from At The Mountains of Madness (1931). Lovecraft explicitly stated the Elder Things were “Men” from the dawn of Earth’s history:

“After all, they were not evil things of their kind. They were the men of another age and another order of being…They had not been even savages-for what indeed had they done? That awful awakening in the cold of an unknown epoch – perhaps an attack by the furry, frantically barking quadrupeds, and a dazed defense against them and the equally frantic white simians with the queer wrappings and paraphernalia … poor Lake, poor Gedney… and poor Old Ones! Scientists to the last – what had they done that we would not have done in their place? God, what intelligence and persistence…Radiates, vegetables, monstrosities, star spawn – whatever they had been, they were men!”

As the Scientific American also observed, the Elder Things were creatures of Deep Time, whereas humanity is a shambling, “Johnny Come Lately” in the Earth’s Geologic Timeline:

“For Lovecraft the geology and the detailed description of the discovered fossils is an essential part to present the idea of deep time, especially the pre-Cambrian, when according to the knowledge of his time no life existed on earth. However the expedition of Dyer discovered in rocks dated to this ancient period the traces of highly evolved creatures, referred only as Elder Ones. They are far superior in their culture, technology and abilities to our civilization, most important they are immeasurable older than humans and Lovecraft’s tale ends with a warning: compared to the almost unimaginably vastness of the age of earth (and these creatures) we should feel quite humble (and afraid)” (24).

Even the Elder Race, wise and ageless and interstellar – the “men” of that Oligocene Age and Deep Time – opened up a scientific Pandora ’s Box when they created the Shoggoths. The organic machines – viscous multicellular protoplasmic masses capable of molding their tissues into all sorts of temporary organs under hypnotic influence…ideal slaves to perform the heavy work of the [Elder Things] community – were supposed to be the ultimate laborsaving devices (25).

The Elder Race, like the Krell from The Forbidden Planet, created the seeds to its own destruction in the name of progress and leisure-enhancement.

If the Elder Things could not foresee their own destruction in the innocuous creation of the Shoggoths, where does that leave the juvenile race, known as Homo Sapiens?

Who do we think we are?

Humanity’s Track Record with Non-Indigenous Species: A Omen of the Future?

Humans constantly introduce non-native species into new environments.

This happens by chance. When human travel or trade, pests from one biosphere are transported to new environments. Or human beings introduce a species into an environment to control another species.

For example, Plantation owners in Hawaii introduced the mongoose to control the rat population that threatened the Sugar Cane industry. Mongooses did little to harm the rat population – they are active mostly during the day, whereas the rat is active at night. Instead, they endangered Hawaii’s dwindling indigenous species.

This happens by choice, when an exotic pet is released into an environment, because it becomes too big or too wild or too expensive for the owner to care for anymore.

For example, Florida spent almost $100 million dollars in 1999-2000 to control non-native plant, insect, and animal species (26).

Exotic pets also escape.

Such a story played out in an episode of the original Outer Limits series.

The “Duplicate Man” (from a story by Clifford Simak) is set decades after the first interstellar expeditions. Henderson James is a wealthy scientist obsessed with studying an intelligent, telepathic, but intractably homicidal alien known as a Megasoid. Authorities deem the life form so dangerous, it is a capital crime to keep a living specimen anywhere near Earth. However, two years earlier Dr. James bribed a starship captain to smuggle a live one to Earth for him.

The story begins when the Megasoid escapes. Fearful that he will not be able kill the monster by himself, Dr. James arranges for an illegal “bootleg” clone, programmed to hunt down and destroy the Megasoid, before the alien procreates (the Megazoid is parthenogenesis) and goes on a killing spree.

If we have difficulties managing inferior species on earth, what chance do we have against equals, such as a Megasoid, or entities farther up the galactic food-chain?

Will America stand another two-hundred years? That was an often-raised question in 1976, the Country’s first Bicentennial.

We now stand thirty-seven years later and the United States faces new threats to its sovereignty.

That is a subject for articles elsewhere.

In reference to Deep Time, human kind is one flickering frame in the movie War and Peace, which runs 484 minutes and totals 696,960 frames (24 frames per second). If humanity stands as one frame, what of America? When Charlton Heston fell to his knees, and agonized over the decapitated Statue of Liberty lying on a beach in the far-flung future (Planet of the Apes):

“Oh my God. I’m back. I’m home. All the time, it was… We finally really did it. You Maniacs! You blew it up! Ah, damn you! God damn you all to hell!” (27)

Why would an American Astronaut expect U.S. icons to last unscathed forever?

In the progression of time, and against the backdrop of Cosmicism, even that classic science-fiction scene results from egotism – Man’s destruction at the hand of Man.

Sumer, Egypt, Rome, Mayan – all these great civilizations fell and their institutions – from Roman Gladiator Games to Mayan Astronomies – turned to dust. Which American institution do we expect to endure – free enterprise? The Constitution?

Or, as in Woody Allen’s Sleeper (1973), will only McDonalds persevere?

And what of outer space? Would America’s obsession with nation-building – an attempt to replicate U.S, governmental institutions in other societies – be a doctrine that extends to the cosmos? If humans colonize space, will they also try to humanize it?

Will Yog Sothoth strike up a chorus of Yankee Doodle Dandy? Not likely. The aliens in fact that mirror the Old Ones in fiction wait.

Eternally they wait.

*****

End Notes:

(1) H.P. Lovecraft’s Letter to Farnsworth Wright, 5 July 1927.

(2) Notes on Writing Weird Fiction By H. P. Lovecraft, Amateur Correspondent, 2, No. 1 (May–June 1937), 7–10.

(3) A Scientific American Blog: “Geology of the Mountains of Madness” by David Bressan, December 17, 2011

(4) Quoted in Michel Houellebecq, H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life (1999), referenced in Andrew Riemer’s “A nihilist’s hope against hope”, 2003.

(5) H.P. Lovecraft’s Letter to Farnsworth Wright, 5 July 1927.

(6) An Essay: “Americanism”, United Amateur, by H.P. Lovecraft, July 1919.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Ibid.

(9) H.P. Lovecraft’s Letter to C.L. Moore, 1936.

(10) An Online Essay: “The ‘Protestant/Calvinist Work Ethic’” by Barbara G. Goodrich, January, 2010. http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~bgoodric/The%20Calvinist%20Work%20Ethic%20and%20Consumerism.htm.

(11) An Essay: “Americanism”, United Amateur, by H.P. Lovecraft, July 1919.

(12) An Online Essay: “H.P. Lovecraft: The Man”, by Dustin Wright, Chaosium.Com, 2003.

(13) Reuters, Herald News, PC World, Washington Post, 6.18.2013, http://www.statisticbrain.com/

(14) Internet Enemies, Reporters Without Borders (Paris), 12 March 2012.

(15) Global Post: How Have Computers Changed the Workplace? By Clayton Browne.

(16) Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100: by Michio Kaku, February 21, 2012.

(17) From Beyond: by H.P. Lovecraft, 1920.

(18) Hyperspace: A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the 10th Dimension: by Michio Kaku, 1995.

(19) From Beyond: by H.P. Lovecraft, 1920.

(20) The Haunter in the Dark: by H.P. Lovecraft, 1935.

(21) The Call of Cthulhu: by H.P. Lovecraft, 1926.

(22) “Alien DNA could be ‘Recreated’ on Earth” The Telegraph, By Claire Carter, 06 Oct 2013.

(23) Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family: by H.P. Lovecraft, 1921.

(24) A Scientific American Blog: “Geology of the Mountains of Madness”, by David Bressan, December 17, 2011.

(25) At The Mountains of Madness: by H.P. Lovecraft, 1931.

(26) An Online Article: “Florida’s Exotic and Invasive Species”, http://www.fpl.com.

(27) An Online Blog: “Planet of the Apes (1968) Quotes”, http://www.imdb.com.

John DeLaughter is a Data Security Analyst who lives in rural Pennsylvania with his wife Heidi, daughter Kirsten, grand daughter Riley, and two cats. He’s devoured Lovecraft, beginning with At the Mountains of Madness in high school. In his spare time, he’s editing his fantasy novel entitled Dark Union Rising.

Discover more from The Lovecraft eZine

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

This was a great read! Thanks John. Spent my Sunday morning reading this, while in the background Face the Nation played out its morbid stories of mall shootings and bombings abroad. Our great human race, huh?

LikeLike

You are welcome Mark, I am glad you enjoyed the article. Yeah, too much Fox, too much Drudge, too much CNN, can really lower your estimate of the human race, The reality of humanity deepens your understanding of where Lovecraft got his Cosmicism, Have a great day!

LikeLike