This post is by John A. DeLaughter, a Lovecraft eZine contributor.

Mommie Dearest was one of the first celebrity tell-all books (later to become a movie starring Faye Dunaway). In that work, Christina Crawford, an adopted daughter of actress Joan Crawford, recounts years of dark traumas she suffered privately at her famous mother’s hands.

The story pointed out how often behind facades of fame and fortune, dwells stories of maternal madness.

Similarly, behind H.P. Lovecraft’s posthumous success as a horror writer lies a horrific upbringing.

In this article, I would like to examine HPL’s torturous relationship with his mother, Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft.

A Brief History of HPL’s Early Years:

Let us begin our conversation with a short history of Lovecraft’s early years. Many events have repercussions on the dynamics of Susie Lovecraft’s relationship to Howard Phillips.

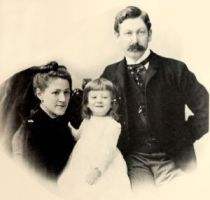

Winfield Scott Lovecraft, HPL’s father, exited his life at age three. The reason: Winfield, fell into a catatonic state, that confined him to Butler Hospital, a Providence psychiatric institution. He later died from untreated Syphilis when HPL was eight.

Howard’s mother, Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft, never recovered from the trauma of her husband’s absence and death.

Widowed at age forty, Susie Lovecraft and her son, Howard, moved into the mansion of his Maternal Grandfather, Whipple Van Buren Phillips. His maternal aunts, his two aunts (Lillian Delora Phillips, 1856-1932; and Annie Emeline Phillips, 1866-1941) also lived there.

The Widow Lovecraft was unable to comfort HPL, because of the coldness of her own Puritan upbringing.

So Lovecraft sought comfort among the ghosts that inhabited the books in his Grandfather Whipple’s attic. Whipple also dotted on young Howard Phillips. Besides instilling in HPL, a love of poetry, his grandpa taught HPL to appreciate and create his own horror stories.

That five years was the closest thing to a normal life HPL ever knew.

Whipple Phillips died on March 28, 1904, when Howard Phillips was thirteen. His Grandfather’s death threw the remaining Phillips into genteel poverty. Financial setbacks forced HPL and his mother to move from the family mansion to a cramped flat.

Lovecraft was devastated by the loss of his birthplace. HPL also lost his closest childhood friends, his Grandfather’s library.

Later Sara Lovecraft, her mental and physical condition deteriorating, suffered a nervous breakdown in 1919. She was admitted to Butler Hospital, where, like her husband, she would never emerge. She died on May 24, 1921.

A Maternal Quagmire: Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft

The Widow Lovecraft’s relationship with her son Howard was complex and problematic. Howard Phillips and Susie Lovecraft’s move to the flat at 598 Angell Street increased the sense of psychological claustrophobia. Lovecraft’s suffocating relationship with his mother intensified.

Susie Lovecraft was an emotionally unstable person.

She was histrionic; little things turned into grand psychological dramas. Her wildly fluctuating behavior, unpredictability, and constant verbal abuse (humans are verbal animals, words cut deep despite the nonsense about sticks and stones especially from parents) traumatized HPL.

HPL lived in a household, where he constantly walked on psychological eggshells, to avoid outbursts from his mom. According to HPL biographers, Susie Lovecraft’s fear of change, and of the world beyond her household, was extreme. (1)

Briefly, think about that phrase, “… [an extreme] fear of the world beyond her household.” Did Lovecraft mirror the same fear instilled in him by his mother, as an aspect of his Cosmicism?

Is Cosmicism: “…a fear of the cosmos beyond humanity’s household, earth?”

Susie Lovecraft’s “Love-Hate” Relationship with HPL:

Susie linked Lovecraft with his father, Winfield, and developed a pathological love-hate relationship with him.

On one level, there is evidence that Susie “hated” her son for reasons we will explore.

On the other hand, Susie Lovecraft “loved” young Howard. As we will see, her version of “loving” HPL was a smothering, overprotectiveness.

Did Susie make Howard Phillips Suffer for the Sins of His Father?

I believe the pattern of Susie Lovecraft’s verbal abuse over Howard’s imagined “deformities” fit the following scenario.

Lovecraft’s mother mistreated Howard because of the “sins of his father”.

Winfield Lovecraft wronged her by catching Syphilis (perhaps infecting Susie too, though that is conjuncture). In the late 1890s to early 1900s, a terrible stigma fell on anyone who contracted a venereal disease. Plus, there was no known cure for the Syphilis until 1908.

Did the Widow Lovecraft know the Syphilitic cause of her husband’s death?

She called HPL “disfigured”, “stoop-shouldered” and “ugly”. A neighbor recounted that: “Mrs. Lovecraft talked continuously of her son who was so hideous that he hid from everyone and did not like to walk upon the streets where people would gaze at him,” a statement the neighbor considered “exaggerated” (2).

Was Susie Lovecraft watching Howard Phillips, to see if he developed facial deformities common to children infected with congenital Syphilis?

She encouraged her son to wear his deceased father’s clothes as a young man. Her delusions transformed her son’s appearance (tall, gaunt, with a long, prognathous jaw and frequently blemished skin) into an image of moral degeneracy.

Was Susie Lovecraft visiting the anger she felt towards Howard’s father on her son, the spitting image of Winfield?

One HPL biographer concluded as such:

“All the evidence seems to point toward the livelihood that Susie came to learn of the nature of her husband’s illness. That she transferred the fear and loathing caused by the illness of her husband onto her innocent son seems indubitable” (3).

In time, HPL internalized those maternal messages, later reliving the trauma they caused in the autographical tale, “The Outsider”.

Susie Spins her Apron Strings into an Inescapable Web of Protectiveness:

Next, fearful that she would lose Howard like she lost her husband, Susan Lovecraft treated her son like an invalid.

Lovecraft’s physical “symptoms” served a dual-purpose in Susie’s psychic economy – they allowed her to “hate him”, for what his father did to her; and they allowed her to “love him”, by maintaining control over him, to prevent her from losing Lovecraft’s father a second time.

Howard’s “sickliness”, real or imagined, fed into that pathology. HPL’s aunts Lillian Delora Phillips and Annie Emeline Phillips, with whom HPL lived out his later years, also coddled him. Their attitudes and actions enforced a stigma that nagged HPL all his adult life. They treated HPL as incompetent, unable to navigate the complexities of adult life without help.

Lovecraft’s mother and aunts’ overprotectiveness demoralized Howard.

His mother fanatical acts coerced HPL out of joining the service in World War I. Lovecraft recalled that event:

“I am feeling desolate and lonely indeed as a civilian…I would try to enter were it not for the almost frantic attitude of my mother; who makes me promise every time I leave the house that I will not make another attempt at enlistment!” (4).

The Widow Lovecraft felt betrayed by her ingrate Son’s attempted enlistment, the son she had done so much for. In her mind, enlistment meant certain death. During HPL’s stab at enlistment, Susie relived the same heightened separation anxieties that terrified her when Winfield Lovecraft was committed.

Howard Phillips’ attempt to cut Susie’s apron strings faltered.

Susie and her sisters also effectively prevented him from getting a regular job. Their suffocating relationships factored into HPL’s inability to complete high school and his nervous breakdown at age 18. They encircled HPL, effectively cloistering him from the outside world. He lived as a hermit until age 23, a virtual vegetable.

In May 1918, he wrote to Alfred Galpin:

“…I am only about half alive – a large part of my strength is consumed in sitting up or walking. My nervous system is a shattered wreck and I am absolutely bored and listless save when I come upon something which peculiarly interests me…”

Then comes the passage that concludes the letter: “Then I perceived with horror that I was growing too old for pleasure. Ruthless Time had set its fell claw upon me, and I was 17. Big boys do not play in toy houses and mock gardens, so I was obliged to turn over my world in sorrow to another and younger boy who dwelt across the lot from me. And since that time I have not delved in the earth or laid out paths and roads. There is too much wistful memory in such procedure, for the fleeting joy of childhood may never be recaptured. Adulthood is hell” (5).

During this time, Lovecraft contemplated suicide. HPL took long bicycle rides and thought about throwing himself into the icy depths of the Barrington River.

HPL almost hung himself on his mother’s apron strings.

Lovecraft sought Solace in Places, not People:

As we have seen, a life-long dependency on others crippled Howard Phillips. That tendency found its basis in HPL’s suffocating relationship with his mother.

When those people let Lovecraft down, by dying or otherwise, he felt devastated. The list of people on whom Lovecraft depended, and later exited his life was long:

- Wilfred Scott Lovecraft – July 19, 1898 (death).

- Whipple Van Buren Phillips – March 28, 1904 (death).

- Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft – May 24, 1921 (death)

- Sonia Greene – January 1, 1925 (moved out, later divorced).

- Lillian Delora Phillips – July 3, 1932 (death).

- Robert (Two-Gun Bob) E. Howard – June 11, 1936 (suicide).

In response, Lovecraft’s own psychic economy, sought a partner that would never let him down. He found an anchor, that stabilizing element in his chaotic existence, not in a person, but in a place.

Providence did not exit HPL’s life, like the adults that he had entrusted himself to. Providence was immortal; people were not. Lovecraft wrote of his preferred attachments:

“…To all intents and purposes I am more naturally isolated from mankind than Nathaniel Hawthorne himself, who dwelt alone in the midst of crowds…The people of a place matter absolutely nothing to me except as components of the general landscape and scenery….My life lies not in among people but among scenes—my local affections are not personal, but topographical and architectural…It is New England I must have—in some form or other. Providence is part of me—I am Providence…” (6).

HPL was not a branch of the Lovecraft or Phillips family tree; he felt more secure as a scion of timeless Providence.

Each Scene was a Séance

Finding permanence in a place also filtered into the psychic background of Lovecraft’s stories.

Lovecraft sets many haunting stories in impressionistic regions. A cobbled street, the peak of a gable roof, a ritual fire that burnt atop a domed “Miskatonic” hill – each scene was a séance. Immortal Providence and her sisters glowed with spirit like a Thomas Kincaid Postcard. Lovecraft’s mystical rapport with his psychic sceneries in rural Massachusetts and colonial-antiquarian towns like Salem, Marblehead, and Rhode Island, infused a mock Transcendentalism in which “spirit” dwells.

The only element that HPL had an antipathy to assigning any residual spirit was human beings:

“…I could not write about ‘ordinary people’ because I am not in the least interested in them. Without interest there can be no art. Man’s relations to man do not captivate my fancy. It is man’s relations to the cosmos—to the unknown—which alone arouses in me the spark of creative imagination. The humanocentric pose is impossible to me, for I cannot acquire the primitive myopia which magnifies the earth and ignores the background…” (7).

The human spirit, glorified by the Enlightenment, meant nothing to Lovecraft. Human beings were no more than:

“…an insignificant bunch of squabbling apes on an insignificant ball of mud that whirls around an insignificant nuclear furnace” (8).

Conclusions of a Victorian Vulcan:

The cosmos was not kind to Howard Phillips Lovecraft.

Most children’s first emotional impressions of the universe arise from his or her maternal relationship:

“When these needs are consistently met, the child will learn that he can trust the people that are caring for him. If, however, these needs are not consistently met, the child will begin to mistrust the people around him. If a child successfully develops trust, he or she will feel safe and secure in the world. Caregivers who are inconsistent, emotionally unavailable or rejecting contribute to feelings of mistrust in the children they care for. Failure to develop trust will result in fear and a belief that the world is inconsistent and unpredictable” (9).

Lovecraft’s world was anything but consistent. His existence vacillated between chaos and control. Chaos caused by the death of people significant to him, constant financial upheavals, and his mother’s dramatic outbursts. And the control, under the watchful eyes of a hovering mother and aunts.

Lovecraft’s Cosmicism is a philosophy born of pain. Early tragedies stripped Lovecraft of the civilized pretenses that allowed many people to escape existential angst. Through his voracious reading, Lovecraft found philosophies that validated the psychological truths of his traumatic childhood.

In light of HPL’s past, Joyce Carol Oates raised the following question:

“Is Lovecraft’s life a tragedy of a stunted, broken-off personality, severely traumatized in childhood, and never to ‘mature,’ or is there a poignant triumph of a kind in the way in which the aggrieved, terror-ized child refashions himself, through countless nocturnal-insomniac sessions of writing, into a purely cerebral being?” (10)

Despite the intellect Lovecraft cultivated, where he tried to become the equivalent of a Victorian Vulcan, Howard found little refuge from the emotions of his painful past. Perhaps, like the fictional half-human, half-Vulcan Spock, Lovecraft forever struggled to eke out a life between the polar extremes of his childhood traumas and his celebrated intelligence.

——————

End Notes:

(1) An Online Article: “The King of Weird,” The New York Review of Books: Joyce Carol Oates, October 31, 1996.

(2) The Providence Journal, August Derleth Correspondence with Clara Hess, a Lovecraft Neighbor, September 19, 1948.

(3) An Essay: “Parents of Howard Phillips Lovecraft”, by Kenneth W. Faig, Jr., An Epicure in the Terrible: A Centennial Anthology of Essays in Honor of H.P. Lovecraft, David E. Schultz and S.T. Joshi, eds., Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1991, p. 70).

(4) H.P. Lovecraft Letter to Rheinhardt Kliener, June 22, 1917.

(5) H.P. Lovecraft Letter to Alfred Galpin, May 1918.

(6) H.P. Lovecraft Letter to Lillian Delora Phillips, 1926.

(7) An Essay, “The Defense Remains Opens,” by H.P. Lovecraft, April 1921.

(8) An Online Article: “The Eldritch Horrors of H.P. Lovecraft”, On This Day, by Mordicai Knode, TOR.com, August 20, 2013.

(9) An Online Article, “Trust Versus Mistrust: Stage One of Psychosocial Development”, by Kendra Cherry, About.com, Psychology.

(10) An Online Article: “The King of Weird,” The New York Review of Books: Joyce Carol Oates, October 31, 1996.

John DeLaughter is a Data Security Analyst who lives in rural Pennsylvania with his wife Heidi, daughter Kirsten, grand daughter Riley, and two cats. He’s devoured Lovecraft, beginning with At the Mountains of Madness in high school. In his spare time, he’s editing his fantasy novel entitled Dark Union Rising.

Discover more from The Lovecraft eZine

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

The title threw me off at first – but after reading the article, it makes perfect sense.

LikeLike

Thank you Blackwingbear. “Mommie Dearest” almost became cultural cliche, with its own negative baggage. But, after reviewing the facts of Lovecraft’s childhood, the raw trauma seemed to fit the title. I’m getting the hang of these replies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you James. There is such a wealth of information surrounding HPL, with the thousands of letters he wrote, outside his body of Weird Fiction. I feel like I only scratch the surface of the man, when developing a piece like this.

LikeLike

Thanks Robert. Yes, too many of us flee our emotions, medicate them out of our awareness, or… We only own up to them, when we get older. Lovecraft stayed true to his inner visions, even when they were so damnably dark. In that sense, he was a visionary, with the courage to follow his artistic path…

LikeLike

Very interesting. Learned a lot!

LikeLike

terrific article. I’m new to Lovecraft as an artist himself and enjoy reading about him. What is most intriguing is H.P.’s persistence and insistence on identity. Even at 17 he was able to isolate his feelings into words — breakdown or no, this is a high degree of self awareness. It takes a great deal of will to deal with one’s demons.

LikeLike