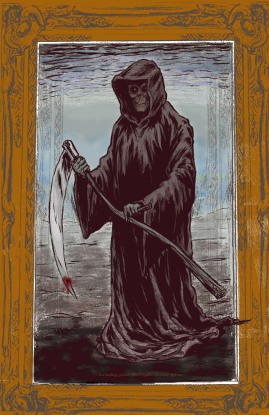

Art by Dominic Black – http://webtentacle.blogspot.com – click to enlarge

The antique woman led him up the ancient flight of wooden steps, and he felt a frisson of enthrallment at being in this place of which he had so often dreamt. It had not been easy, saving the money that enabled his flight to Paris – but he knew, that moment, that the effort had been entirely worthwhile. They reached the top landing and stood before the door to the infamous garret room, where the withered beldame hesitated before pushing the key into its lock.

“It is strange, Monsieur. I always feel – I don’t like disturbing the quiet of this room. It’s silly, I know, but I always expect it to be occupied – by him. You would think that his suicide would have given the room an aura of death and gloom, but instead one feels – his youthfulness. They portrayed him horrendously in that silly film. I’m originally from England, and had no idea of the man’s legend when I married my French husband, may he rest in peace. The artist’s legend began to grow in your own country, when Hollywood decided to film their fabricated story of Honoré Radin. And now you tell me that you are writing a biography of the painter.”

“A novel, Madame Dupin. The success of the recent horror film related to his notorious painting and its supposed curse has generated a lot of interest in the artist himself. I’m unqualified to write an authentic biography, fiction being my métier; and, in truth, so little is known about Radin that an actual account of his life would be a very short book.”

“And so you’ve come to his garret room in Paris to help you in creating its – quality?”

“It’s ambiance, just so.”

The elderly woman nodded, and then she shrugged slightly and turned the key in its lock. She did not walk into the room herself, but rather motioned to it with one frail hand. “Entrez, Monsieur Blake.” The young man moved past her, into the room, and in so doing he imagined that he had stepped into another world, an elder realm. The woman at the doorway continued talking. “When the people from Hollywood came to film the opening sequence they spent a fortune restoring the apartment to how it might have looked on that evening of 1848. They succeeded rather well, as you can see. The gaslights, the faux antique furnishings. I’ve removed the hangman’s noose they fastened to the beam – that was a bit much. Oh, yes, it was in our contract that they would leave the room exactly as they restored it – it was the only payment we required, knowing as we did that we could then charge the curious to visit the chamber.”

But he could not heed her, for he was absolutely focused on the painting above the mantelpiece.

“This is the replication they had painted?”

She nodded. “You know, of course, that they acquired the original for when they filmed the sequence of Radin’s suicide. That was a wild day. They actually invited me to portray the original propriétaire in the film, but I simply couldn’t be in the same room with that – thing in oil! This imitation doesn’t capture the aura of the original. We had steep security that day – the museum would let us have the oil for one day only – because of the painting’s reputation. Of course you know of the lunatics who feel that the picture is evil, and of the attempt to destroy it at the museum where it is now kept locked away in some secret chamber. I stood here as they were installing the original in its place – and I felt such foreboding. The room took on a different atmosphere.” Although his back was to her, the young writer could sense the shudder that convulsed her petite frame. “Well, I’ll leave you to your work.”

He turned to wave to her and saw that he was alone, and suddenly he was seized with an absurd sense of panic. He did not want to be alone in the room, that garret of silence and shadow and memory. Some of the artist’s original belongings, so it was rumored, were still in the room, which his queer old landlady had locked up and refused to rent after the painter’s suicide. Looking up, the novelist gazed at the ceiling beam on which the rope had been secured that had helped the artist extinguish his mortality – an act that, now, had ushered the painter into a kind of immortality, because of the lurid legend of his painting and its curse. An element of that legend lingered in the room, centering on the replica of the notorious oil.

The writer walked to a tall bookcase and studied the titles of its books, most of which were in French. Surely these could not be the actual books belonging to Radin, who had been rumored to traffic in sorcery and black magick. The novelist had studied languages at Miskatonic University, where he had become engrossed in the library’s assembly of arcane lore. Thus the titles on the shelves before him were familiar. He touched the spine of the Comte d’Erlette’s Cultes des Goules and did not like how slick he found the binding, as if its boards had been soaked in sweat. He whispered other titles: Gaspard du Nord’s thirteenth-century translation of the Book of Eibon, and the strange Sorcerie de Démonologie. Pulling out a sheaf of bound foolscap he trembled in discovering it to be the highly obscured French translation of the Necronomicon, a copy of which had disappeared from a thirteenth-century monastery in Southern France. No, these titles could not be authentic, they must be clever props manufactured by the movie people.

And yet it was not unlikely that the painter had indeed owned such a library, for he had boasted in correspondence to his father of having trafficked with the dread god Thanatos, and one of the legends surrounding the artist was that his suicide had been his final sacrifice to that dark deity. This part of the legend had been magnificently if luridly portrayed in a dream sequence in the Hollywood film; but as he stood in that room the writer knew that the movie had not explored the depths to which Radin had been a connoisseur of the daemonic arts, and this realization caused him to turn now so as to contemplate the pièce de résistance of Honoré Radin’s celebrity.

The infamous painting had been entitled “The Grim Reaper,” and it was whispered that whoever owned the painting met with violent death, and that their demise was preceded by a warning from the painting itself, in the form of a stigmata that appeared on the Reaper’s blade. He stepped closer to the canvas and touched his hand to the scythe’s curved blade, and as he did so he felt a genuine chill of terror evoked by the mastery of Death’s portrayal. He then noticed, scrawled in russet French script, a line of verse at the bottom of the painting, which he recognized as belonging to one of Shakespeare’s sonnets. His brain quickly translated:

“And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defense…”

Was this transcription part of the original painting? There had been no reference to it in the American horror film based on the legend of the painting’s curse. Was this the key to Radin’s maniacal occult quest: immortality?

Blake turned to peer into one murky corner of the room, where a tall object had been enshrouded with a sheet of black cloth. He guessed what the thing was from having seen the film so many times. This, too, would figure in his novel based on Radin’s mad life and secret  death. Going to it, he clutched the cloth and dramatically yanked it to the floor. Before him stood the framed full-length mirror that had, he knew, been within the room since that drear evening in 1848, when the artist had tied one end of his hangman’s rope to the ceiling beam. Blake stared at the figure that had been painted onto the mirror’s surface, and the chilly room grew colder. Before him, in muted colors and hazy detail, the mad artist had painted his self-portrait. The thing was almost complete, except for the very lowest portion of the trouser legs and shoes, which were missing. It gave Blake the curious impression that the life-size figure had stepped into and beyond the surface of silver glass. How uncanny, to stand before this image, which added a peculiar feeling of presence to the room. It was as if the painter’s frozen reflection had been caught into the chemistry by which the mirror had been constructed.

death. Going to it, he clutched the cloth and dramatically yanked it to the floor. Before him stood the framed full-length mirror that had, he knew, been within the room since that drear evening in 1848, when the artist had tied one end of his hangman’s rope to the ceiling beam. Blake stared at the figure that had been painted onto the mirror’s surface, and the chilly room grew colder. Before him, in muted colors and hazy detail, the mad artist had painted his self-portrait. The thing was almost complete, except for the very lowest portion of the trouser legs and shoes, which were missing. It gave Blake the curious impression that the life-size figure had stepped into and beyond the surface of silver glass. How uncanny, to stand before this image, which added a peculiar feeling of presence to the room. It was as if the painter’s frozen reflection had been caught into the chemistry by which the mirror had been constructed.

The painter had been a handsome fellow. The American film had portrayed Radin as a man of early middle age, but if this mirror-image was exact, the artist had been as young as Blake himself. Only the eyes seemed aged, seeming like those of one who had gained, through nefarious study, a world of rare knowledge, if not wisdom. The young man’s face, as it had been painted, , was very pale; and Blake noticed a place at the forehead where the mirror’s surface had been slightly scratched, forming a kind of weird webbed symbol in the middle of Radin’s brow. Blake studied the hands held down at the artist’s sides, palms outward, and it perplexed him to see, in the middle of one palm, the self-same symbol that had been scratched onto the mirror; but the symbol on the palm was a part of the painted image.

Blake stared into the beauty of the artist’s eyes. The portrayal’s lips were parted slightly, as if about to whisper some rare words. From somewhere in the room a breeze began to stir, which drifted to the novelist and sighed into his ear. Blake knelt upon his knees and studied the image on the palm, as shadows began to shift behind the painted figure. Not understanding what motivated him, Blake closed his eyes and pressed his mouth against the painted palm.

Wind rustled at his ear. It kissed him. The palm moved away from his mouth and wove its fingers into his hair. He could sense moving shadows on his eyelids. The hand in his hair tightened its hold and lifted him to a standing position. Was it the velvet wind that kissed his eyes so softly, that chuckled so lowly? Blake opened his burning eyes and could not comprehend the whirling void in which he found himself. It was a place outside of time and space, a realm between stars and bedlam. It was not untenanted. All about him Blake could sense an all-observant incorporeal presence. It brooded before him, blasphemously, haunting darkness. It mocked him with its mirthless laughter. It took form as an unholy silhouette that crept near to him like some disordered flaw, a spectre wrapped in a robe of obsidian degeneracy.

He shook with fear yet could not turn away. The strange dark one smiled with a cynicism that scorned mortality; and when it raised one hand Blake shivered as the void decayed, as time degenerated. Nothing escaped the crawling chaos. Blake watched, and understood immortality. An essence of the soul would linger always, rootless and ruined, in the deterioration of everything. The novelist wanted to clamp shut his eyes, but could not; and thus he watched as the phantom before him reached into the void and brought forth two pale orbs. Blake somehow knew that they were the last dying stars of ruptured heaven, and he wept to see how feebly they sparkled. He gasped as the Outer One struck the stars together so that a bolt streaked from them, shooting toward the thing of clay and bone and blood. He felt the symbol that was burned upon his brow and, finally, was able to turn away from nightmare and scream for mercy. Before him he beheld a sheet of glass. He gaped through that glass, into a gas lit chamber that was untenanted. He saw, vaguely, his reflection and the symbol that pulsed with light on his forehead. With lunatic force, he smashed that forehead against the sheet of glass.

Madame Dupin heard the crash from within the shunned room. She paused before the door, wondering why it has been closed. At last she pushed at the door and grimaced at the smell that wafted to her, the smell of some vile burning thing. She hesitated again before creeping cautiously into the chamber. How faintly the gaslight flickered, as if it cowered from some ghastly manifestation. There was no one within the room, and yet the elderly woman was certain that the young man had not vacated it. Her first shock came when her eyes rested upon the replication of Honoré Radin’s noxious canvas – for there, smeared on the image of the Reaper’s blade, was a thick smear of ichor, a stinking mess that might have been Night’s bloodstain. The room’s stench emanated from that smear. Turning from the hideous sight, she saw where the mirror’s glass had shattered, littering the floor with shards. How could this happen, to a relic that had endured for so many decades? What had the American done inside the room, and where was he concealed? She bent to pick up one piece of glass, on which there was the painted image of a hand. She held it tenderly until she noticed the trickle of blood that moved down her finger. How odd, to see the way her blood, slipping toward and onto the portion of mirror that she held, was somehow absorbed into the property of the glass. She threw the piece of mirror from her.

The ancient creature then noticed movement on the floor, a dark image that seemed to flex on the largest shard that lay among the detritus of shattered mirror. Bending low, her bloodstained hand picked up the weighty shard and stared at the face that shuddered in its depths. She did not understand why the painted image, which she knew should have been that of the suicidal artist who had hanged himself inside the room so long ago, was now that of the room’s recent visitor, the novelist Blake. When that visage flapped open its bruised lips and uttered a wounded howl, Madame Dupin fled the room forever as the large shard of enchanted mirror, dropped from her shaking hand, shattered into little bits.

Wilum Pugmire has been writing Lovecraftian weird fiction since the early 1970s. Over the past decade he has concentrated on book production, and is the author of Some Unknown Gulf of Night, Uncommon Places, The Strange Dark One, and Bohemians of Sesqua Valley. With Jeffrey Thomas he wrote Encounters with Enoch Coffin, and with David Barker he wrote The Revenant of Rebecca Pascal. His next book will be Spectres of Lovecraftian Horror, a collection written with David Barker.

Wilum Pugmire has been writing Lovecraftian weird fiction since the early 1970s. Over the past decade he has concentrated on book production, and is the author of Some Unknown Gulf of Night, Uncommon Places, The Strange Dark One, and Bohemians of Sesqua Valley. With Jeffrey Thomas he wrote Encounters with Enoch Coffin, and with David Barker he wrote The Revenant of Rebecca Pascal. His next book will be Spectres of Lovecraftian Horror, a collection written with David Barker.

If you enjoyed this story, let Wilum know by commenting — and please use the Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus buttons below to spread the word.

Story illustration by Dominic Black.

Pingback: “To Kiss Your Canvas” – MarzAat·

Beautiful, dark imagery, reminiscent of the master himself. Well done.

LikeLike

great story!!!! I love how well you caught the feel of his writing.

LikeLike

Great stuff. Always look forward to new Pugmire. Bursting with pride to share a ToC.

LikeLike

Edit: …overuse of the name Henri for changing it to Honore…

LikeLike

It is great to finally see this in “print” after your tease of it on your blog. Your prose, as always, is beautiful poetry.

Two questions: Is there any particular reason other than (in my opinion) overuse of the name Henri to Honore? Would you mind if I pretend this building is on the same street as Erich Zann’s?

LikeLike

Excellent! I loved the vivid setting, the atmosphere and pacing, and the beautiful language in this piece. A bit like a Mythos homage to Dorian Gray. Satisfyingly disturbing. 🙂

LikeLike

pretty nice. thank you

LikeLike